The Echoes of Artifacts in “All That She Carried”

Just like Tiya Miles, historian at Harvard University and author of All That She Carried, I grew up in Cincinnati, a city where history, voices and ghosts enter without knocking. For Miles, these echoes are held within her Great Aunt Margaret Stribling’s quilt, for me it is my great grandmother’s silver spoon, and for an enslaved woman named Ashley, it was a cotton sack. These ancestral artifacts, Miles argues, hold not just the power of memory, but act as spiritual and tangible evidence of survival.

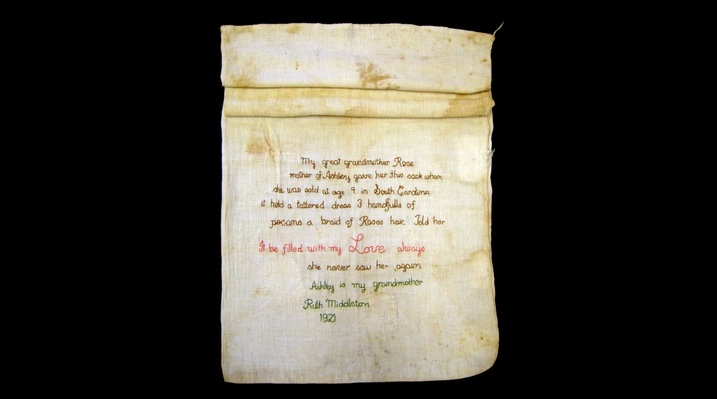

All That She Carried centers around one object—Ashley’s Sack; an embroidered cloth sack given from an enslaved mother named Rose to her nine-year old daughter Ashley when she was sold away. The sack contained a dress, a handful of pecans, and a braid of her mother’s hair. The sack was passed all the way down to Ruth Middleton, Rose’s great-granddaughter who in 1921 while living in Philadelphia embroidered the following words:

My great grandmother Rose

mother of Ashley gave her this sack when

she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina

it held a tattered dress 3 handfulls of

pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her

It be filled with my Love always

she never saw her again

Ashley is my grandmother

Ruth Middleton

1921

In the early 2000s the sack was purchased at a flea market for $20 in Nashville. It now sits at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, on loan from the Middleton Place Foundation in Charleston. The sack motivates the book—a lyrical meditation, an excavation of lineages of black women’s thought and practices of survival. Meeting at the nexus of African American Studies, environmental history, and material culture studies, All That She Carried unearths the multiple textures of black women’s experiences, from enslavement to Jim Crow. Light on the jargon and academic opacity, the book reads smoothly, transitioning rhythmically and occasionally poetically from the past to the present.

Miles is additionally the author of a historical fiction book, and her recent research has been invested in an oral history of ghosts. Her use of language often erupts with juicy descriptions and viscerality. Readers will become acquainted with classic slave narratives such as Harriet Jacobs, and other lesser-known figures such as Eliza Potter and Melnea Cass. These sources operate to produce a “chorus of corroboration.” This chorus also includes contemporary black women writers such as Alice Walker, Gayle Jones, Toni Morrison and Octavia Butler. Due to the archival limitations of the sack itself, these other voices operate to bring clarity to the daily lives and experiences of Black women across time and space.

This creative use of sources is greatly influenced by the work of historian Marisa Fuentes, author of Dispossessed Lives, and critical theorist Saidiya Hartman. Fuentes’ method of “reading along the bias grain” and Hartman’s “critical fabulation” play a critical role in the analytic work of All That She Carried. In this methodological shift, Miles follows a turn within the field of Black women’s history which looks to stretch the contours of the archive “to identify the bias grain…the place where the records can be stretched to reveal still more.” Though Miles speculates and creatively uses sources she works with a methodology of care. This care is found in her deliberate and careful attention to detail working to not reproduce any harm to her historical subjects.

All That She Carried locates the spiritual and tangible archive in objects, places, and literature. This is not traditional history; here emotions are held with the same care and consideration as traditional sources. The goal is not simply to uncover the story of Ashley’s sack, but to unpack the meaning of material things in Black women’s lives from enslavement through Jim Crow segregation. How did these material items enable the cultivation of community? Things, objects, and places preserved over time show familial continuity. Miles compels us to consider how objects hold a certain metaphysical space where memories and emotions meet, making them valuable and transformative sites for scholarly focus.

Following the book’s title, the items within the sack, those which were carried, narrate our journey through Black women’s history. This study of material culture illuminates how the dress packed by Rose reflects how enslaved women used everyday objects to resist structures of oppression. The handful of pecans show the importance of the land and specifically Black ecological inheritance. These items also worked to contradict the system of slavery itself by erasing the illusion that enslaved people were themselves property. The terror of familial separation shines through the specific items Rose left for her daughter—some items provided sustenance and protection, while the braid of hair is a tender expression of motherly love and familial ties which slavery attempted to dissolve. For Black families, a group which has historically experienced material precarity, objects hold and symbolize family, survival and strength.

In an attempt to extend the ethical lessons of Ashley’s Sack to our current moment, Miles tends to rely on over-generalizations, stretching the cloth sack across the nation too far beyond its specificity. This decision towards generalization at times erases the specificity of enslaved women’s realities, and the complexity of our past, in favor of a kumbaya-esque “national reckoning” ethos. She cast this historical moment of terror and violence in an instructive manner—arguing that Rose’s story and “Black women of our past can be teachers.” I agree that our ancestors provide tools and strategies to navigate our current reality but caution attempts at removing these lessons from their historically specific context. The beauty in All That She Carried is found in the specificity of Ashley’s Sack and the surrounding narrative which Miles eloquently reconstructs. Black women’s voices, things and lineages deserve space to exist separate from moral imperatives.

Overall, All That She Carried is the epitome of an artifactual Black women’s history, one which begins with a cloth sack but ends with the bodies that held it. The significance of the material object grows from it’s communion with the bodies of Rose, Ashley and Ruth. Their corporal engagement becomes as much of an archive as the cloth sack itself. Miles provides a thoughtful and poignant look into the power of one object in telling the story of a people. Whether a silver spoon, an ancestral quilt, or a cloth sack, these artifacts as archives can change the way history is conceived and shared.

— By Mimi Borders. Read the review as it appears in Chicago Review of Books.