Working Paper on Black and Native Historical Intersections

In the fall of 2017, undergraduate students in the University of Michigan Course, “Blacks, Indians and the Making of America,” taught by Dr. Tiya Miles, took up a set of questions posed by organizers in The Majority Coalition of the Black Lives Matter Movement. The Majority is a people of color-led coalition that was initiated by the Movement for Black Lives, which includes Black Lives Matter Global Network and dozens of groups working in the 21st century Black freedom movement. In an effort to better collaborate with indigenous organizers in a principled and informed way, The Majority reached out to scholars working on Black and indigenous issues. This paper is a response to that request.

The class that engaged in this work was a diverse, majority people of color group made up of individuals who identified as: Arab, Black, Black/Choctaw, Cheyenne River Sioux/Italian, Latino, Mashpee-Wampanoag, Middle Eastern, Mixed-race/Black, Palestinian/Syrian/North African, Seminole/white, white, and/or queer. The students divided into four small groups over the course of a semester to research and write on the five questions below (after folding question 3 into question 4) and then presented their work to the class before revising. The groups’ responses to the questions follow in essay form. The writers’ names appear in the order of their section of the essay. The group papers were substantially edited by Tiya Miles, then a professor of American Culture, Afroamerican & African Studies, History and Native American Studies at the University of Michigan and Dylan Nelson, a History Department Honors graduate of the University of Michigan. Funded by a University of Michigan M-Cube collaborative grant awarded to faculty members Tiya Miles, Joseph Gone, and Paulina Alberto, Dylan Nelson augmented this report with additional research, writing, and interpretation in keeping with the class collective’s views in the winter and spring of 2018. In the summer of 2018, Utibe Gautt Ate and Tresa Horney joined the project as additional editors.

Working Paper on Black and Native Historical Intersections

A Project by Students at The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor 2017-2018

Editors: Tiya Miles, Dylan Nelson, Utibe Gautt Ate, and Tresa Horney

Student Writers: Sharie Branch, Torin Clay, Regan Detwiler, Silan Fadlallah, Harry Furey, Emily Johanson, Obayda Jondy, Telana Kabisch, Jasmine Rahming, Davis Schuberth, Miles Smith, Samara Jackson Tobey, Cheyenne Travioli, Michael Weathers, Mario Zuñiga

Writer-at-Large: Dylan Nelson

Questions Taken Up by the Class

1. What was the nature and extent of Indian/ Black collaborations? Of Indian/Black unity?

2. What was the extent of Native Americans’ ownership of slaves?

3. What was the extent of Black involvement in the wars against Indian people?

4. How do indigenous claims for land rights factor in the current residents of the land?

5. What critical turning points should current solidarity movements be aware of?

Sections

Query 1: Collaboration and Unity

Query 2: Native Slavery

Queries 3 & 5: Wars and Turning Points

Query 4: Land Rights and Settler Residency

Query 1: Native and Black Unity

Mario Zuñiga, Michael Weathers, Harrison Furey,

Obayda Jondy, Silan Fadlallah, and Dylan Nelson

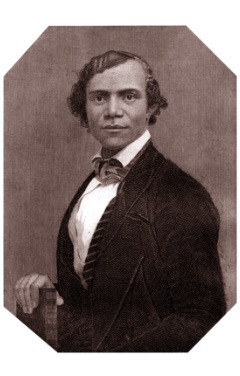

Crispus Attucks

Crispus Attucks, a man of Black and Native descent, was the first casualty of the Boston Massacre, an altercation between American colonists and British soldiers that sparked the successful Anglo-American colonial rebellion of the late 18th century. Attucks was born to an enslaved Black man and an American Indian (likely Natick or Wampanoag) woman. In Boston, Attucks worked on British ships, a job he disliked in part due to the felt presence of British military personnel.[1] With tensions between the Boston community and British soldiers on the rise, Attucks and others gathered into an unruly crowd and expressed their anger to a group of British soldiers. The soldiers fired into the crowd, hitting Attucks, who died on the spot. The story of Crispus Attucks was soon forgotten, and it would be decades before his activist legacy was written into history.[2]

Attucks’s role in the Boston Massacre was ignored for roughly seventy-five years until the abolitionist Frederick Douglass published a report from a Convention of Colored Citizens held in Rochester, New York, in April 1851 in his newspaper, The North Star. The report proclaimed: “How the fact will be yielded to that effect – the fact that the first martyr, Wm. Attuck [sic], the first man that fell in the Revolutionary struggle, fighting in vindication of the fact of the equality of man and in defence of the rights of man, in favor of the idea of brotherhood, was a black man; gloried be his name!”[3] This notice elevated Attucks as a figure of African American history, but Attucks’s Native identity continued to be ignored or dismissed as inauthentic,[4] underscoring the importance of acknowledging and celebrating the Afro-Native whose death remains a symbolic and visceral origin of America’s aspirations for independence. Attucks, in his person and identity, was a forbear whose model of resistance to oppression can be taken up by both African Americans and Native Americans today. Crispus Attucks was a radical of both Black and indigenous heritage, and for that reason we give him due attention in our study. The fact that his parents linked hands across racial lines indicates that interracial family-making is a potential means of mutual support and survival.

The Seminole Wars

Concerted and widespread political collaboration between Blacks and American Indians is initially most evident around fifty years after the Boston Massacre, during the Seminole Wars of the 19th century, when they faced a common enemy: land-hungry American settlers and slaveholders backed by federal military might. Before the Seminole Wars, Spanish Florida served as a sanctuary for enslaved Blacks. Those who could escape American slavery from southern states like Georgia and South Carolina found refuge there while Blacks enslaved by the Seminoles often faced more lenient masters than their white counterparts. In Spanish Florida, escaped Blacks created a place called the Negro Fort under the auspices of the British military, a stronghold that, for a time, combated slaveholder power in the region. After American soldiers under the directives of General Andrew Jackson destroyed the fort in 1816,[5] Black fugitives found themselves living with the Seminoles along the Suwannee River.[6] In August 1817, American General Edmund Gaines sent a request to Chief Kenhadjo, leader of the Mikasuki band of Seminoles, to retrieve fugitive slaves that resided on his territory. In a brief, defiant response, Kenhadjo refused and implicated his band in the ensuing conflict.[7]

The First Seminole War began in the late fall of 1817. The most prominent Seminole village in Georgia at the time was Fowl Town, which was directly adjacent to the Florida border and about fifteen miles from the American Fort Scott. As activities at Fort Scott increased, Neamathla, the chief at Fowl Town, warned American officials not to cross the Flint River boundary for timber and other resources. Insulted by Neamathla’s assertion of sovereignty, Gaines ordered an unsuccessful attack on Fowl Town to capture Neamathla. Soon after, in late November 1817, Fowl Town suffered another assault. Though Neamathla again escaped, around twenty Seminoles died, the village was pillaged and burned, and the community at Fowl Town was permanently displaced. Seminole retaliation was swift. One week later, an American ship heading toward Fort Scott—which also carried women and children and many sick and injured soldiers—was ambushed by Seminole and Black warriors. Most of the ship’s passengers perished in the attack and open conflict thereafter was guaranteed.[8]

A few months later in the spring of 1818, Andrew Jackson arrived at Fort Scott with a large force of Tennessee volunteers, Georgia militiamen, and Lower Creek warriors. Jackson and his men attacked and destroyed Indian towns at Tallahassee and Miccosukee and numerous villages, looting and destroying 300 homes along the way. These assaults thoroughly devastated the Seminoles, leaving them homeless and scattered throughout the nearby swamps. Upon learning that the Spanish governor at Pensacola had offered hundreds of Indians shelter and supplies in May 1818, Jackson turned west. Despite the Spanish commander’s invocation of U.S. President Monroe’s orders to deal only with Indians, Jackson easily took Pensacola and Fort Barrancas.[9]

In the months and years that followed, Seminoles, Creeks, and Blacks of overlapping ancestries lived in motion. The First Seminole War eliminated territorial refugia that had once offered Black and Indians a semblance of security, and in February 1819, the Adams-Onis Treaty, which ceded Florida to the United States, eliminated hopes that Black and Indians might find Spanish or English imperial partners to resist further American aggression. On September 18, 1823, Seminole leaders at Moultrie Creek signed a treaty that dissolved all their territorial claims in Florida and created a land-locked reservation. By design, and like all other federal treaties, the Treaty of Moultrie Creek left Seminoles and Blacks even more vulnerable. The agreement stipulated relocation to what Florida governor William Pope DuVal described as “‘the poorest and the most miserable region I ever beheld.’” Relocation left Seminoles dependent on the United States for provisions, which was used to leverage the return of enslaved runaways who had sought refuge in Indian communities and across formerly Spanish Florida.[10]

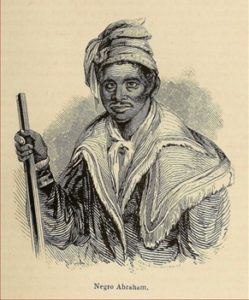

In the years between the First and Second Seminole Wars, a Black Seminole named Abraham grew to prominence. He eventually gained favor with the chief, Micanopy, and accompanied him as an interpreter for a Seminole delegation to Washington in 1826. Leading perpetually liminal existences, Black Seminoles were uniquely situated to serve as interpreters and cultural brokers. Like his contemporaries, Abraham became well known for his intellect, cunning, and his ability to influence Seminole leaders. For example, when violence again erupted in the 1830s, Abraham made secret war preparations and urged enslaved Blacks on Florida plantations to join the Seminole front.[11]

Following the Indian Removal Act in 1830, the U.S. Department of War sent James Gadsden to negotiate the Treaty of Payne’s Landing with the Seminoles in the spring of 1832. As part of Andrew Jackson’s program to remove all Indians west of the Mississippi River, this treaty proposed to relocate the Seminoles to the Creek Reservation in what was then the Arkansas Territory, to dissolve the Seminoles into the Creek Nation, and to return all escaped Blacks to their “lawful owners.” Abraham served as an interpreter for a November 1832 delegation of Seminole leaders that travelled to inspect the offered land, but there was very little support among Seminoles in Florida for the treaty. In addition to unease and frustration over brief and coercive negotiations, historian Kenneth W. Porter suggests that Black Seminoles “were the determining factor in the Seminole opposition to removal.”[12]

Over the course of the next few years, negotiations between Seminoles and federal agents generated further frustration and division within the Seminole community. Even so, for the most part, the Second Seminole War emerged out of collaboration between Blacks and Indians resisting their relocation and enslavement by the United States government.

In late December 1835, Seminole forces attacked several plantations in northeastern Florida, leading white settlers to flee in panic and to free hundreds of enslaved Blacks that then joined the fight. The Dade Massacre of December 28, 1835 was the first act of organized Seminole violence since the First Seminole War in 1818. The ambush on interloping white settlers was carried out by a group of 180 Seminole warriors, at least 50 of whom were Black Seminoles. This battle resulted in a decisive Seminole victory: the warriors left only two survivors in the white settlement while losing just three of their own men.[13]

Black and Indian forces did not have the same good fortune in conflicts thereafter. By 1837, some 8,000 American troops had descended on central Florida and captured Black people and horses, burned villages, and made planting and harvesting crops nearly impossible for the Seminoles. In March of 1837, Seminole leaders gathered at Fort Dade to negotiate terms of peace and a reservation near Tampa Bay.[14] General Thomas Jesup, leader of US troops in Florida, understood that collaboration between Blacks and Natives was a threat to US power structures. In an 1836 letter to Secretary of War Benjamin Butler, he wrote that this conflict was, “a negro, not an Indian war,” that would be felt in the enslaved population of the South if not quashed swiftly.[15] Jesup initially agreed that the Black allies of the Seminoles would accompany them on their journey westward, but white plantation owners demanded that they surrender the Black population for labor. When the Seminoles rejected this condition, peace talks came to an abrupt halt. In this instance, Black and Native collaboration kept the conflict alive, as the Seminoles would not accept peace at the cost of their Black allies’ freedom.

Blacks and Seminoles continued to resist the U.S. military even after the capture of prominent leaders, including Micanopy, until 1842, when they secured their right to remain in Florida in peace negotiations. This victory for the Seminoles was a pyrrhic one: in seven years of conflict, the Seminole population in Florida dwindled from 5,000 to around 600.[16] By the end of the Third Seminole War in 1858, American officers believed there were less than 100 Seminoles in Florida. The actual figure was likely between 300 and 400, but of those Seminoles remaining in Florida, many later fled to Indian Territory in Oklahoma or retreated to undesirable land in the Everglades and the Big Cypress Swamp.[17] The fate of Blacks in Florida was similarly grim. In a declaration on June 28, 1848, U.S. Attorney General John Y. Mason wrote that, “Negroes should be restored to the condition in which they were prior to the intervention of General Jesup.” President James Polk agreed and downgraded the standing of Black Seminoles, who had been free since the 1837 reversal of peace, to the status of Seminole slaves. With their freedom stripped, the Black Seminoles, under the leadership of John Cavallo and Wild Cat, prepared for a journey to Mexico, where slavery was no longer legal.[18]

The history of the Seminole Wars provides crucial insight into the nature of the pernicious grip of US military imperialism over North America and the multiracial coalitions that have challenged it. The core of these conflicts was formed by conflicting notions of land and resource use, competing sources of sovereignty, and contestations over the boundaries and leadership of cultural, racial, and political communities. In the early stages of these conflicts, Seminoles and Blacks found themselves in the crosshairs of rival imperial powers whose investment in them was blatantly self-interested. As the United States emerged as the preeminent power in North America, Indian warfare in Florida had two related goals: Native land dispossession and the capture of Blacks. These were pragmatic and philosophical goals, initiating the theft of Black labor while strengthening a caste system that was enshrined in the US judicial and legislative systems. Left in abject poverty on unworkable land, Seminole communities sought the type of recognition by those systems that would entail little more than being left alone. Yet because the American project depends on perpetual conflict between lower castes, US military and bureaucratic action in Florida demanded intimate dependence that sought to stifle distinct cultural forms and interracial collaboration.

The outcomes of the Seminole Wars were devastating. It is essential to remember the contrast between the impossible demands made of Blacks and Indians and the utter inability, and ostensible disinterest, of the American republic to hold accountable the commanders and negotiators that represented their society. On multiple occasions during the Seminole Wars, Blacks and Indians were forced to choose dignity and fraternity over survival and financial security. Their resilience and creativity were not only a testament to their brilliance and courage, it outlined models of survivance and prosperity in a system built on their suffering.

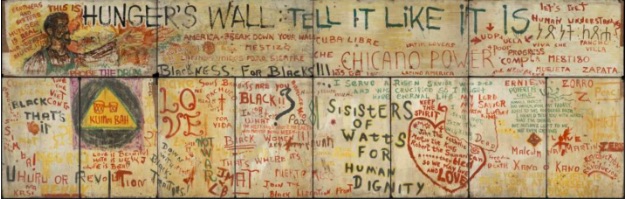

Black and American Indian Activism

Cooperation between Blacks and American Indians on the front lines of political struggle emerged in symbolic and more tangible ways in the 1960s and 1970s as waves of activism swept the nation. Blacks, American Indians, and other minority groups were united by histories of violent oppression at the hands of the United States government, high rates of poverty and very limited economic opportunities, negative and misleading representations in popular media and culture, and state and federal governments that routinely failed to meet the needs of non-white communities. In the late 1960s and 1970s, a culture of resistance took inspiration from numerous non-white activists and artists, and occasionally multiracial coalitions expressed far-reaching concerns of marginalized groups in the United States.

The African American social movement for Civil Rights developed over long decades, culminating in the 1950s and 1960s with a series of protests organized around nonviolent action. Arguably the most visible and symbolic moment of the civil rights movement was the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, at which Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famed “I Have a Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial to somewhere between 200,000 and 300,000 people, at least 75% of whom were Black. The March on Washington became the template for massive demonstrations in the capital and required the type of broad coalition-building that was sometimes at odds with more sustained and local civil rights organizing.

Tensions between marginalized groups were especially visible five years later during King’s Poor People’s Campaign, in which he shifted away from a predominant focus on African Americans to assemble a “multiracial army of the poor”[19] aimed at holding the Johnson administration accountable for the promises of the War on Poverty. While the Poor People’s Campaign has often been described as a disastrous or ineffective feature of King’s legacy (he would not live to see the actual campaign)—and it was undoubtedly shaped by open conflict within and between the various ethnic groups assembled—historian Gordon K. Mantler demonstrated that it was an unprecedented moment for multicultural and interregional organizing. While organizing protests and negotiations for two months in the spring of 1968, poor people of Mexican, African, American Indian, Puerto Rican, and European descent lived together in an erected shantytown referred to as Resurrection City and at the alternative Hawthorne School in Washington D.C. Sharing space, food, and responsibilities; exchanging perspectives and dreams; and marching together allowed activists of innumerable designations to broaden their networks, refine critiques and compare strategies, and envision entirely new futures and communities that they could fight toward. During those months, Hank Adams, an American Indian of Assiniboine and Sioux descent who became one of the most important organizers and negotiators for Indian activism in the 1970s, organized a multiracial sit-in surrounding the U.S. Supreme Court building to protest a recent ruling on fishing rights in Native waters. Mantler argues that events like these, which drew criticism from the press and were challenged by some Black leaders, allowed nonblack leaders to assert themselves in the activist landscape and move beyond their mostly symbolic role up to that point.[20]

In the years before the Poor People’s Campaign, discontent with the nonviolent tactics of veterans of the civil rights movement was rising throughout the country, including among Blacks. Dissatisfaction was especially prominent among youth and influenced the birth of the Black Power Movement, which was first established by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and advocated for Black freedom, security from state and vigilante violence, and Black economic strength. Black students created SNCC as a platform to vocalize the concerns of the younger members of the Black community. The group was pivotal to the 1961 Freedom Rides, which pushed to desegregate buses, and were also active in the freedom marches and sit-ins carried out by Dr. Martin Luther King. With the help of the director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Ella Baker, SNCC distanced itself from the non-violent values preached by Rev. King. However, it was not until the Mississippi Freedom Summer, during which three members of SNCC (one Black man and two Jewish men), were murdered at the hands of the KKK, that party members began to turn to more violent means of self and community defense.[21]

Founded in October 1966 with communist ideals based on revolutionaries Che Guevara and Mao Zedong, the Black Panther Party for Self Defense used mass organizing and community-based programs to provide the Black community the rights they had been denied. Most importantly, the Party formed to address police brutality through militant self-defense. In their declaration titled, “What We Want Now,” the Black Panther Party expressed the following demands: “We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice, and peace.”[22]

The Black Panther Party took steps to carry out their demands by creating two key programs. The first program was established to signify the militant presence of the Black Panthers by organizing armed patrol units to follow police movements in Black neighborhoods. Each Black Panther soldier on patrol was equipped with a weapon and black leather uniform, signifying their organization and readiness.[23] The second program centered around community service, creating free educational classes, child development centers, food pantries, medical clinics, employment centers, and much more.[24] By taking these dramatic steps to build up communities, the Black Panther Party was able to gain widespread support from neighborhood residents, to the extent that by 1970 they had thirty chapters and were operating out of most major American cities.[25]

Not long after the development of the Black Panther Party, the federal government began to investigate the expansion of the armed group. As African American Studies scholar Charles E. Jones explains, “The party’s commitment to armed self-defense and revolutionary politics made it an inevitable target of government attention.”[26] In 1967, the FBI operation known as COINTELPRO shifted its focus from the civil rights movement to the Black Panthers. The acting director of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, declared the Black Panther Party to be “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country.” From then on, the Black Panthers began to implode as the FBI utilized propaganda to display them in the worst possible light, insinuating that the deaths of Black Panther Party members resulted from police acting in self-defense. Tellingly, the FBI saw the Free Breakfast Program for Children and the Black Panther Party Newspaper as the most potent threats.[27]

The FBI leveraged disagreements within the party, using false propaganda and informants to create internal conflict that then led to the creation of two rival factions. Huey Newton began to discredit members of the party whom he deemed disloyal, including one of the most influential members, Eldridge Cleaver. By the early 1970’s the Black Panther Party had lost most of its political power.[28] However, the demise of the Black Panther Party was not the end of the Black Power Movement, which strove continuously to ensure the safety and empowerment of the Black community.

The Black Panthers became an inspiration and a model for some Native American activists, notably the American Indian Movement (AIM), which led the most visible resistance campaigns in the 1970s. However, like the civil rights movement for African Americans, Native American activism emerged long before AIM and the Black Panthers captured national attention. Beginning in the 1940s, federal and state legislatures began pursuing a policy that is now referred to as termination, which no longer recognized tribal governments, suspended government aid, privatized Native lands and resources previously held in common, and compelled Indians to assimilate into mainstream American cultural and economic practices. In response in 1944, Indians from across the country formed the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) in a departure from organizing that had previously occurred almost exclusively along the lines of tribe and treaty. As a legislative advocacy group, the NCAI played an instrumental role in eventually bringing termination to an end and in protecting Native rights and cultures by helping secure the passage of laws like the 1975 Indian Self-Determination and Education Act, the 1968 Indian Civil Rights Act, and the 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act.

Grounded by tribal membership and the concerns of reservation communities, the NCAI adopted a firmly bureaucratic approach to Indian advocacy and sought to distinguish Indians from the assertive, riotous tactics embraced by many activists in the 1960s. Indeed, even as late as 1967 the NCAI flew a banner that proudly read “Indians Don’t Demonstrate.”[29] As a matter of historical fact, this was not accurate, and it became increasingly inconsistent with the sentiments of many, if not most, Indians. In the 1950s, thousands of Indians that were relocated from reservations to urban areas as part of the federal assimilation program were able to encounter other Indians from around the country on city streets, community centers, and college campuses. Urban Indians in this period energized and helped develop a more robust pan-Indian movement, organized into student groups and local lobbying groups, and staged smaller protests that sometimes attracted violent responses from government officials.

The protest cohort of Native activists came into stride during the 1960s. In the summer of 1961, American Indian college students from around the country gathered in Gallup, New Mexico, to form the National Indian Youth Council (NIYC). Under the leadership of Ponca Clyde Warrior, the NIYC began to aggressively expose the violence and hypocrisy of government agencies like the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the self-interested cowardice of certain tribal elites that aligned themselves with federal administrators.[30] Before heading to New Mexico, Warrior spent the summer of 1961 working with SNCC’s voter-education project in rural Black communities in Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi.[31] Warrior’s collaboration with Black activists not only contributed to the more revolutionary rhetoric and tactics adopted by the NIYC, it reflects how Black, Indian, and other minority activists increasingly saw their movements in solidarity with other victims of white supremacist imperialism and how ideas and strategies developed in partnership.

The term “Red Power” began to circulate and gain traction in the mid-1960s. Though the phrase is often attributed to Vine Deloria Jr., it was used by NIYC members at least as early as 1964.[32] Imagined in response to and in collaboration with the Black Power movement, Red Power activism was marked by an uncompromising fight for justice and freedom on Indian terms. In 1964, the NIYC came to the support of the Muckleshoot, Puyallup, and Nisqually tribes in Washington state in their longstanding conflict with state and federal governments over fishing rights. In March 1964, NIYC members helped stage a “fish-in” with local Indians in which they “illegally” fished in waters of Puget Sound that Indians had fished for decades. The NIYC attracted renowned actor and activist Marlon Brando, who was arrested along with other protestors and was among around 1,000 Indians and non-Indian supporters who marched on the Washington state capital of Olympia.[33] Throughout the protest, NIYC collaborated with the Survival of American Indians Association, a radical, local group committed to civil disobedience led by Janet McCloud, who would go on to form Women of All Red Nations and is considered the “Rosa Parks of the American Indian Movement.” Though McCloud’s militancy earned her criticism from tribal governments, the demonstrations proceeded with increasing support and favorable attention from major media.[34] As was true for Black, Chicano, and other marginalized populations by the mid-1960s, American Indians began to demand bolder efforts to expose and hold accountable the power structures that maintained their suffering. While the fish-ins expanded the scope of what Indian activism could be, internal tensions and negotiations between tribal and state officials, as well as protests that often turned violent even as Marlon Brando and other non-Native supporters moved on, saddled the effort.

The most explicit and potent initiation of the Red Power movement was the nineteen-month occupation of Alcatraz Island in the San Francisco Bay from late 1969 to 1971. Eventually adopting the name Indians of All Tribes, occupiers set a model for future Indian activism that repeatedly took possession of federal land, highlighted the ongoing history of unfulfilled treaty obligations, and transformed those lands in the service of cultural, educational, economic, and legal empowerment. The Alcatraz occupation was by far the most visible Indian protest up to that point. Both press coverage from the time and scholarship since have tended to focus on the leadership of men like Richard Oakes, the occupation’s spokesperson, and John Trudell, a future AIM luminary who ran the island’s radio broadcast.[35] Such accounts have neglected the core organizing activities that kept the occupation alive, namely the running of the community kitchen, school, and health center, roles executed overwhelmingly by American Indian women. Moreover, they have overshadowed the importance of women leaders like LaNada Means, who remained on the island for the entirety of the occupation and wrote the $300,000 grant proposal to turn the island into an Indian cultural center, and Stella Leach, who oversaw the island’s health center.[36] While the occupation eventually ended without Indian reclamation of Alcatraz Island, it permanently altered the tenor of Indian-white relations as termination came to an end, the 1970s brought forward several pieces of pro-Indian legislation, and Americans across the country of all racial and ethnic affiliations became attuned to the unique and urgent concerns of their American Indian contemporaries. Most importantly, as ethnic studies scholar Donna Langston Martinez (formerly Donna Hightower-Langston) carefully observes, Alcatraz “galvanized Indian pride and consciousness, and heralded a new era in American Indian activism,”[37] in which self-determination and self-sufficiency were no longer symbolic goals.

The most famous Red Power organization, the American Indian Movement (AIM) soon filled the crucial space the Alcatraz occupation created. Paul Chaat Smith (Comanche) and Robert Allen Warrior (Osage), co-authors of a seminal history of the Red Power years, Like a Hurricane, describe the name AIM as, “Perfect because it sounded authoritative and inclusive. Perfect because it suggested action, purpose, and forward motion…The initials—A-I-M—underscored all of that, creating an active verb rich in power and imagery. You aimed at a target. You could aim for victory, freedom, and justice.”[38] Founded in July 1968 in Minneapolis, AIM began as a definitively urban organization concerned with police brutality and disproportionate rates of incarceration among Indians. Two of AIM’s founding members, Dennis Banks and Clyde Bellecourt, did time in the state Stillwater Prison shortly before the organization’s founding. While incarcerated, both men contemplated their pasts and Indian heritage to arrive at new visions of Indian politics that could deliver liberation outside the scope of an assimilated respectability. This stance came to embody AIM’s actions and directly connected them to the Black Power and antiwar movements whose efforts to reimagine American society were coming to a head at precisely the same moment. AIM’s efforts began deeply rooted in place. Like the Black Panther units described above, the AIM Patrol included cars equipped with radios, cameras, and tape recorders to monitor arrests by police departments and Indians in red jackets that congregated in bars and street corners where police were dispatched. AIM soon began to facilitate legal support, emergency loans, employment services, and housing. AIM leaders were adept at negotiating with cops, city officials, church leaders, lawyers, civil rights activists, and journalists. They also advised churches, educators, and antipoverty programs on how to incorporate Indians respectfully and effectively. By 1971, several local chapters had formed across the country that earned AIM a reputation for protest and media spectacle.[39]

In the years that followed, AIM took that reputation to unprecedented levels with two of the most audacious and equivocal media sensations of the 20th century: the 1972 takeover of the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ (BIA) headquarters in Washington D.C. and the 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation. In collaboration with several American Indian organizations including the National Indian Youth Council and the Native American Rights Fund, AIM organized the Trail of Broken Treaties, which brought caravans beginning in Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles on a trip across the country in the fall of 1972 to highlight historical injustices and a host of issues facing American Indian communities. The Trail, which converged on Washington D.C. the week before the 1972 federal elections, was modelled on the 1963 March on Washington and was the largest American Indian demonstration in the capital up to that point. Poor planning and miscommunication left activists without lodging, and amid the restlessness and confusion, activists seized the BIA building. In the six days that they occupied the BIA, activists trashed and looted the place, destroying documents and the building that had facilitated the theft of Native lands and cultures as well as government programs that failed to provide livable conditions. When riot police attempted to forcibly remove protesters, a human barricade of multiracial supporters prevented their entry. Activists left the building on November 9th after receiving some travel expenses and without having successfully negotiated their demands with federal officials. The boldest act of anti-colonial resistance that American Indians had taken since the 19th century achieved no tangible policy goals and diminished perceptions of Indian protests among the American public, but nevertheless left many Native people emboldened and crystallized resolve against the treacherous and inept Bureau of Indian Affairs.[40]

In the several weeks that followed, some activists on the Trail returned home but many continued through Indian Country to preserve the movement’s momentum. In January, AIM members met with Chicano activists in Scottsbluff, Nebraska (which bordered the Pine Ridge Reservation), to plan a common strategy in the region. In early February, a riot erupted in Custer, South Dakota, over the trial of the murderer of the Sioux Wesley Bad Heart Bull.[41] AIM members and other American Indian radicals had turned toward the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota for a variety of reasons, but probably foremost among them was the tyrannical reign of the tribal chairman Dick Wilson, whose private army routinely committed arson, beatings, and murder. As AIM members gathered in the region, the United States Marshals Service, the FBI, and the BIA all increased personnel on the reservation and worked in coordination with Wilson.[42] AIM had been invited to Pine Ridge by older women from the reservation community who had led public dissent against Wilson. They conceived the occupation of the hamlet of Wounded Knee as a poignant reclamation of the site’s murderous history. In the 71-day occupation that began on February 27, 1973, over 70% of the occupiers were Indian women, who dug bunkers, carried weapons, ran the medical clinic, and performed countless other tasks. The cohort of Indians negotiating with government officials was composed mostly of elder women such as Gladys Bissonette and Ellen Moves Camp. The occupation of Wounded Knee was a blatant rejection of U.S. imperial history and institutions, and the threat to the government was apparent in the severity of their reaction. Not only did the occupation provoke a military response complete with tanks and frequent exchanges of gunfire, the end of the occupation also brought on 1,200 arrests and 275 cases in federal, state, and tribal courts.[43] In the following years, representatives of the American state held activists in detention and pursued seemingly endless legal proceedings that served to deflate, disorient, and delay organizing by AIM and others. A total of 185 indictments and two years of trials led to only 15 convictions on minor charges.[44] Most frighteningly, having failed to remove chairman Wilson through both legal and extralegal channels, dissidents faced two years of terror following the occupation in which 250 Pine Ridge Indians, mostly traditionalists, and 69 AIM supporters were killed.[45]

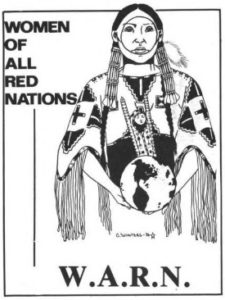

The legacy of the Wounded Knee occupation played out in the years and decades to come and the spirit of Red Power did not die in South Dakota in 1973. In 1974, American Indian women, many of whom had been active in AIM, formed Women of All Red Nations (WARN) to address the distinctly gendered experiences produced by a paternalist and colonial U.S. government. WARN described themselves as being devoted first and foremost to decolonization and placed solidarity with all American Indians above collaboration around “broader” or “more important” issues.[46] While the expansive revolutionary energy of the late 1960s and early 1970s had greatly enhanced the work of AIM, NIYC, and other Native organizers, Natives continued to be alienated by the logics and expectations of the white, liberal democratic institutions to which they were forced to appeal. As American Indians’ treaty rights began to be met in earnest and Red Power organizing made self-determination more of a reality throughout the 1970s, a public and legislative backlash followed. By 1978, Congress was considering several bills that would have reversed many of the achievements of the previous few years. This prompted the last major event of the Red Power movement, the Longest Walk. After a ceremony on Alcatraz Island, thousands of American Indians set out on a trek across the country to symbolize the forced removal of the 19th century and to draw attention to the anti-Indian bills in Congress. Unlike many Red Power protests, the Longest Walk was explicitly nonviolent and was as focused on spirituality as politics. Once marchers reached Washington D.C. in July, they maintained a congenial camp where whites, Blacks, and an array of American Indian people enjoyed workshops and talks on Native cultures and history. Perhaps especially because of its peaceful and collaborative tone, the Longest Walk attracted a wide range of supporters that included boxer Muhammad Ali, actor Marlon Brando, comedian Dick Gregory, and musicians Richie Havens, Stevie Wonder, and Buffy Sainte-Marie (Plains Cree). None of the eleven proposed bills passed.[47] While the Longest Walk marked the end of the Red Power era, this highly visible demonstration of solidarity was proof that Black, American Indian, and Chicano activists in the previous two decades had developed robust resistance mechanisms.

Query 2: Native American Slave Ownership

Regan Detwiler, Dylan Nelson, Sharie Branch, Cheyenne Travioli, and Miles Smith

Race in Native American Communities

Americans today are most familiar with what historian Juliana Barr refers to as the “monolithic, chattel-oriented system of coerced labor”[48] that now represents the whole of captivity experiences. However, it is necessary to place any analysis of Black and indigenous bondage into relevant historical and cultural contexts. Throughout the history of North America, motivations for captive-taking and slavery varied across cultures, time, and space. To begin to understand how Native communities came to exert transgenerational bondage on people of Black and Native ancestry, and how and why they executed a wide range of captivity practices, it is important to trace the origins and transformations of racial categories in those communities.

Many scholars have traced indigenous captive-taking practices back centuries to demonstrate that the use of human bondage for material, political, and emotional purposes was not foreign to Native people. For example, historian Daniel K. Richter describes the practice of “mourning-wars” among the Iroquois Confederacy of the Great Lakes region, an alliance dating back to the 12th century. Iroquois war parties raided traditional enemies (indigenous peoples who were not part of the Iroquois League of Peace and therefore stood outside of kinship obligations) to secure captives that might face ritual torture and execution, remain with the Iroquois as laborers, or be fully adopted and virtually replace recently deceased Iroquois people. These practices helped bereft Iroquois grieve, supplemented lowered populations, and maintained social cohesion.[49] Indigenous groups throughout North America had similar practices such that captives regularly confronted many possible fates. Native people captured by other indigenous groups sometimes experienced dramatic shifts in personhood and collective identity. Adopted captives, or their progenitors, might eventually become prominent members of their new communities.

As with most aspects of cultural, political, and economic life, indigenous captivity practices changed with the new and increasing pressures brought on by European colonization. While discussing the Creeks of present-day Georgia and northern Florida, historian Christina Snyder offers a succinct and generalizable statement: “Among the Creeks, captivity was an ancient institution, but it was also a dynamic one. Captives faced a variety of fates ranging from ritual torture to full adoption. The continuum of Creek captivity provided for a highly adaptable cultural institution able to address changing social and economic needs from pre-colonial times until the nineteenth century.”[50] The political-economic and psycho-cultural transformations that white supremacist imperialism brought to indigenous communities are best understood in dynamic local contexts shaped by specific ecological and economic developments.

Sociologists Michael Omi and Howard Winant argue that European conquest was the “first” and “perhaps the greatest…racial formation project.”[51] Rather than linear causation, slavery and racism were mutually reinforcing means toward white supremacist ends, the double helix of plunder and hate directing the economic, political, and cultural synthesis of the modern world. Historian Tiya Miles explains how racial consciousness developed across colonial history, first taking shape in the association between all forms of non-whiteness with slavery and depravity.[52] Indeed, indigenous peoples were systematically enslaved from Detroit to Brazil to New Mexico.[53] However, after decades of armed conflict and the proliferation of “Old World” pathogens, European invaders found it increasingly impractical to enslave Natives, and people of African descent became the preferred source of forced labor. Especially in what would become the United States, Blackness and Indianness became co-determined categories that outlined the hierarchy upon which the society was premised. Tracing through America’s foundational mythologies, Miles demonstrates how this racial “meaning ‘management’ employed by imperial regimes and their subjects,” “locate[d] Indians and Blacks at differential distances from whiteness, Americanness, and the promises of democracy.”[54] As racial categories became increasingly legible throughout the eighteenth century, Natives and people of mixed heritage leveraged and modified their identities and customs based on the proximity to whiteness it afforded them. One custom that seemed to offer advantages was the enslavement of Blacks.

If the methods of enslavement that some Europeans used were unusual to many Natives, their ideas of race would have been foreign as well. Indigenous peoples before and during colonization understood themselves to be part of extended kinship networks that dictated social obligations. Lineage determined imagined identities along the lines of families, clans, or tribes. As Miles notes, “The prevailing understanding was consistent: if your relatives were Indian, so were you.”[55] Moreover, as mentioned above, a person might enter new kin networks and assume multiple tribal identities over the course of her life. Especially on colonial frontiers and borderlands, individual and collective identities were fluid and often shaped by culture more than biology or even inheritance.

The life of Ojibwe woman Susie Bonga-Wright outlines some of the extraordinary opportunities that existed in these liminal spaces. A community leader among the Leech Lake Ojibwe during the late 19th century in present-day Minnesota, Bonga-Wright had African ancestry. Before Episcopalian missionary involvement in this community in the 1870s, the Ojibwes considered the Afro-Ojibwe Bonga family to be French. Susie Bonga-Wright’s grandfather was educated in Montreal, and the family was made up of literate, Christian, multilingual fur traders. Bonga-Wright’s generation of the Bonga family saw themselves as Ojibwe and was accepted as such by their fellow Ojibwe community members, showing that the Bongas’ African ancestry[56] did not inhibit them from fully belonging. George Bonga, Susie Bonga-Wright’s father, was a fur trader who had a robust and positive relationship with the Leech Lake Ojibwe throughout his lifetime. Bonga-Wright earned respect in her community because of her ability to cater to white Episcopalian missionaries’ expectations for Ojibwe women while still prioritizing the needs and goals of the Ojibwes, who were already under serious threat in the face of Euro-American expansion. This made her an ideal candidate for marrying Charles Wright, an Ojibwe-Episcopal deacon and Ojibwe political leader. However, by this time, anti-Black racism had penetrated Ojibwe society. Despite Susie Bonga-Wright’s strong reputation in her community, Euro-American and Ojibwe men challenged her leadership and credibility based solely on her African ancestry. However, Charles Wright and Susie Bonga-Wright did eventually marry, and they sustained their respectable reputations among both Episcopalians and the Leech Lake Ojibwes.

Following the marriage though, Bonga-Wright stopped going by that surname. Instead she went by her Ojibwe name, Chimokomanikwe, or “Mrs. Nashotah,” an anglicization of her husband’s Ojibwe name, Nijode. The switch suggests she wished to conceal her mixed-race identity; particularly her African ancestry. Such strategies were likely common. A century earlier in South Carolina, the evangelist John Marrant became a national sensation after publishing his captivity narrative from his time with Cherokees, a document that did not indicate that Marrant was Black and made a concerted effort to Indianize him.[57] While stories like Marrant’s and Bonga-Wright’s affirm the more favorable cultural currency lent to Indianness, the very idea of the Indian as unrefined anachronism emerged to settle white Euro-American discomfort with the human and cultural costs of their imperial program. As conditions for Natives became increasingly precarious and interactions between whites and Indians took on new dimensions throughout the 18th century, anti-Black racism became an act of preservation. This was especially clear in the Catawba Nation of the Carolinas. Historian James H. Merrell explains how for around 200 years Catawbas perceived Blacks and whites to be part of the same culture. Sharing language, trade goods, and other customs that were all foreign to Catawbas, Blacks and whites were imagined to be partners in the conquest of the “New World.” Consequently, Catawbas’ treatment of Blacks varied: they attacked some, adopted or sheltered some, and traded with others. By the beginning of the 19th century, British and then American settlers established control of the Southeast. In the final decades of the 18th century, Catawbas had become reliant on Euro-American goods and had been exposed to many more Black people than in the century and a half before. Merrell describes the development of racism among Catawbas: “Faced with cultural extinction, Catawbas discovered that hating Black people was one way to avoid being considered Black themselves. This attitude became a fundamental part of Catawba identity, fostering something of a siege mentality that helped perpetuate a communal Indian consciousness. From a personal rather than a collective standpoint, ownership of a slave (and, more generally, contempt for Afro-Americans) helped a Catawba alleviate the pain of being a marginal person pitied, despised, or ignored by the dominant society.” By the middle of the 19th century, Catawbas vehemently denied any association with Blacks, intimate or otherwise, and by the mid-to-late 20th century, contempt for Blacks was described as “a Catawba tradition.”[58]

The Catawbas were by no means the only Indians to strategically adopt anti-Black attitudes. While they remained in the margins, Indians and the ideas people had about them had critical functions in the racially stratified imperial society whose roots were firmly in place by the 18th century. Indigenous treatment of Blacks ranged from torturous and permanent enslavement to intermarriage and full integration into kinship networks. Since the end of the Civil War, previously enslaved people and their descendants have had a wide variety of experiences in the Native communities that once enslaved them. Freedmen and freedwomen of Indian nations and their descendants have struggled to gain citizenship in those nations, and even when citizenship is granted, Native communities can withhold full acceptance.[59]

Creeks, Seminoles, Choctaws and Chickasaws

In the American Southeast (present-day Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, and the Carolinas), the Creek and Seminole nations enslaved Black people. Before the official separation of Upper Creeks and Lower Creeks from Renegade Creeks (Seminoles) in the Redstick War of 1813-1814, practices of the emerging slave trade “fit in neatly with Creek practices” that involved capturing and dispatching war criminals along with selling women and children to newcomers in the area.[60] Throughout the middle and late 18th-century, the Black population in the region grew and eventually exceeded the white and Indigenous population. As plantation slavery spread its roots throughout the Southeast, Creeks became increasingly active in the slave-trading market and more combative with French and British settlers.[61]

Historian Claudio Saunt argues that throughout this expansion of plantation slavery, Creeks lived near a growing population of enslaved Blacks that they mostly encountered as “employees” or “servants” at local trading markets and as runaways seeking refuge. Contact in such an atmosphere led Creeks to acquire increasing numbers of their own Black slaves and to adopt anti-Black attitudes, which were compounded by gendered interpretations of the nature of labor. Black men performed agricultural tasks that Creeks perceived as feminine domestic work, and this reified attitudes that denigrated both Blackness and femininity.[62] Nevertheless, throughout the 18th century, Creek support of slavery provoked internal tensions and created a central conflict within the Nation. By the 1790s, Lower Creeks and Seminoles typically integrated Blacks into the community, though not always as “equals,” and wealthier slave-owners maintained stronger boundaries between their Black slaves and Indian residents.[63]

Enslavement of Blacks in Chickasaw and Choctaw territory (primarily northern Mississippi & western Tennessee, and southern Mississippi and Alabama, respectively) followed similar patterns with some important differences. Much like the Creeks and Seminoles, Choctaws and Chickasaws first encountered Blacks primarily as runaways from nearby plantations who were seeking refuge within Indian territory. As the culture of southern plantation slavery grew in every direction, Choctaw and Chickasaw leaders consistently engaged with European beliefs of racial inferiority and hierarchy and became involved in the industry of Black capture, trade, and enslavement.[64] Like those enslaved by whites, Blacks held as slaves by Choctaws and Chickasaws inherited their status matrilineally and were therefore left without legal or social rights.[65] By the mid-19th century, certain laws strictly prohibited relations and marriage between Choctaw Indians and Blacks, but simultaneously allowed white men to “marry in to the nation.” Even after “emancipation” in 1863, the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations were unwilling to follow through with promises of citizenship and land claims specified in the Treaty of 1866. Tribal governments also adopted laws similar to U.S. southern “Black Codes” pertaining to vagrancy, which virtually reproduced slavery by another name.[66]

Testimonies of Cherokee Slavery

In the 1930s, employees of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) Federal Writers’ Project interviewed Black and Afro-Native people who had been enslaved by Cherokees. In these accounts, ex-slaves described their “mixed-blood” identities in various ways and offered a sense of Native American and Afro-American relations during slavery.[67] At age eighty, Milton Starr stated the he was born “right in [his] master’s house” on Cherokee Jerry Starr’s farm. Milton lived among Cherokees during his childhood and recalled that though he was born enslaved, he received “special” treatment because he was “half-blood Cherokee.”[68] Since he did not face violent discipline and remembered being treated like a member of the slaveholding family, he chose to remain in the Cherokee Nation with his father and stepmother after the Civil War. Milton’s experience wasn’t universal, but it also wasn’t unique, as the condition of a person of African descent enslaved by Cherokees often depended on his or her racial heritage and familial connection with tribal members. Jane Coursey, Starr’s mother, enslaved in Tennessee, was “picked up by the Starr’s when they left that country with the rest of the Cherokee Indians. She wasn’t bought just stole by them Indians.”[69] Unlike Milton, Jane Coursey chose not to remain among the Cherokees upon being freed and instead returned to Tennessee, possibly to reconnect with her own birth or adoptive family.

Henry Bibb, a former slave of Cherokees and future abolitionist, also chose to leave Cherokee territory when he saw an opening. In the Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb An American Slave, Bibb describes the character of the Cherokee man who owned him for a time as reasonable and humane. Bibb makes a point of omitting his Cherokee slaveholder’s name while freely revealing the names of his previous white owners. In a rare first-hand account of Cherokee slaveholding practices, Bibb wrote: “The Indians allow their slaves enough to eat and wear. They have no overseers to whip nor drive them. If a slave offends his master, he sometimes, undertakes to chastise him; but it is often the case as otherwise, that the slave gets the better of the fight, and even flogs his master.”[70] Bibb stated that in the household and community where he was enslaved, husbands, wives, parents, and children were not forcibly separated through sales. In his representation, enslaved Blacks had the leeway to stand up to Native masters without life threatening recriminations. Despite what he represented as more favorable conditions among the Cherokees, Bibb fled his Indian master’s home after the man’s death, adamantly preferring freedom to captivity in any cultural context. While Bibb’s is the only known account of Black slavery in the Cherokee Nation related in a full-length slave narrative, his is not the only recorded experience of enslavement by Cherokees. WPA interviews as well as diaries of Moravian missionaries located on the James and Joseph Vann plantation in present-day Georgia reveal large Cherokee-owned plantations where coercion and violence were used to control the enslaved.[71] Testimonies by those formerly enslaved in Cherokee country varied, indicating a variety of experiences and conditions.

Women and Gender in Slavery

“She was what I call a tyrant. I lived with her for several months, but she kept me almost half of my time in the woods, running from under the bloody lash,” said Henry Bibb of his white mistress.[72] Recollections like these by Bibb and others by enslaved women offer an elaborate account of race relations in the antebellum south and the psychological, emotional and physical terror that women slaveholders, both white and Native, inflicted.

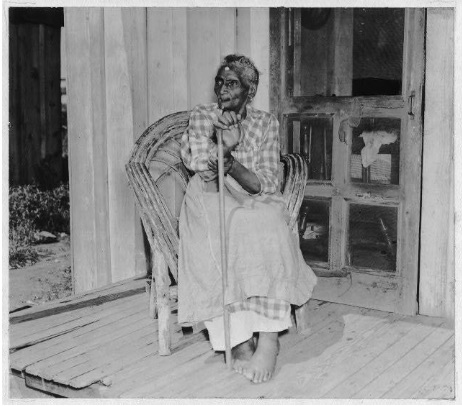

In Out of the House of Bondage, historian Thavolia Glymph writes: “Mistresses and masters (and overseers) described slave women as lazier, filthier; more shiftless, slatternly, ignorant and impudent than slave men; more inclined to theft and lying; less easily managed; less trainable; and in a strategic blow, less interested in their children and their responsibilities as mothers… Mistresses responded to this resistance by cajoling, scolding, hitting and beating.”[73] Several WPA narratives from 1937 illuminate Glymph’s research. For example, Mary Lindsay was interviewed in Tulsa, Oklahoma at age ninety-one. At a time when enslaved people worked in the house or the field, Lindsay did both: “I have to git up at three o’clock sometimes, so I have time to water the horses and slop them hogs and feed the chickens and milk the cows, and then git back to the house and git the breakfast.”[74] She recalled that once granted freedom, despite her inability to pay them wages, her mistress hoped that with the promise of lodging, food and better treatment, Lindsay and other slaves would remain on the plantation. However, “after while,” Lindsay, “asked her ain’t she got some money for me, and she say no, ain’t she giving me a good home?” Such manipulation reveals how mistress-slave relationships exploited the enslaved.

In Fort Gibson, Oklahoma, at age ninety, Chaney Richardson also spoke to the WPA. She was born on Cherokee land near Tahlequah, Oklahoma. When she was around ten years old, her mother was brutally killed. According to Richardson’s testimony, her mother disappeared for a week following an evening when her master expressed concern about young male Cherokees riding around the community in the evening. Richardson described the horror of what happened: “They find her in some bushes where she’d been getting bark to set the dyes, and she’d been dead the whole time. Somebody hit her with a club and shot her through and through with a bullet too. She was so swollen they couldn’t lift her up and just had to make a deep hole right alongside her and roll her in it she was so bad mortified.”[75] Soon after the murder, without explanation, her master sold her brothers and sisters. Years later, she reunited with them, yet for years following the end of the Civil War, Richardson continued to work on the plantation without pay.

Sarah Wilson, also in Fort Gibson, Oklahoma in 1937, described herself as a former Cherokee slave as well as a Cherokee freedwoman. She lived in Arkansas on the farm of Master Ben Johnson, a white man who married a Cherokee woman. Master Ben Jonson was her grandfather. Her father was Johnson’s son, and her mother was a slave. Initially, Sarah’s mistress named her Annie, after herself, but eight years later when the mistress died, Sarah’s mother changed her daughter’s name. Before the mistress’s death, Sarah’s mother beat her if she answered when called Annie. Yet Sarah also faced beatings from her mistress if she ignored her calls. Wilson’s family lived in a one-room structure, her brothers’ and sisters’ beds tucked into the wall like shelving. She shared that if her master was displeased with an enslaved person, he forced them to watch slave-hangings at the courthouse. Sarah also witnessed him beat her uncle until he “fainted away and fell over like he was dead.”[76]

However insightful and powerful, the WPA slave narratives reveal a fragmented history of lack and loss that these women suffered at the hands of captors that were both women and men. In her book, Ties That Bind, historian Tiya Miles articulates the emotional consequences of such incomplete stories. While discussing a Black woman named Doll owned by a Cherokee man named Shoe Boots who also fathered Doll’s five children, Miles writes: “Doll left nothing behind that attests to her character, her strategies and ideologies, the quality of her days and years.”[77] Histories like the ones cited here begin the process of recovering and honoring lives like Doll’s and direct us toward new ways of remembering the complicated, contradictory, and intentional lives of those who lived as the legal property of others.

Query 5 & 3: Critical Turning Points in Afro-Native Histories

Telana Kabisch, Jasmine Rahming, Torin Clay, and Dylan Nelson

The American Revolution

Historian and colonial studies theorist Patrick Wolfe writes about the deliberate and interdependent creation of libertarian ideals and slavery in the American colonies. Race provided white people exemption from moral rules regarding African-Americans and Native Americans. Racial categories were created to oppress those defined as “other” and were bent throughout history to include and exclude groups depending on the need for labor or land.[78]

For most of the colonial period, Native people far outnumbered colonists and exercised considerable influence over them. Often at the mercy of Native people’s goodwill and local knowledge, colonists were compelled to comprehend and appeal to indigenous understandings of the world. The degree and nature of meaningful cultural exchange between Europeans and Natives is a more expansive topic than this paper can address, but clearly European notions of race, hierarchy, and civilization were refined throughout the colonial period and widely replaced other ways of knowing in the “New World.”[79]

The American Revolution weakened the authority of Native communities in the East and further entrenched Black slavery in the South even as some states in the Northeast moved toward gradual emancipation. The war permanently disabled Native groups from fighting colonial encroachment on their land. The American revolution began in 1775 over rising tensions between the British and the thirteen colonies.[80] Multiple circumstances spurred its genesis. For instance, after the French and Indian War, the British began to impose high taxes on the colonial settlements to pay back their war debts. The British strictly regulated trade and many necessities became highly taxed. The British had also issued the Proclamation of 1763 in the wake of Pontiac’s Rebellion in the Great Lakes region. This decree, highly unpopular with American settlers, set the Allegheny Mountains as the western limit of British settlement.[81]

Native communities and individuals played vital roles in the Revolutionary War. They fought on both sides working as spies, diplomats, soldiers, military leaders, scouts, and guides. Through their involvement, Native people sought to secure their lands from further colonial invasion by showing loyalty to either side. Some Native communities chose to fight with the British because their demonstrated investment in limiting colonial expansion suggested they would have greater respect for Indian territorial tenure. Others chose to fight with the colonial rebels because they hoped to maintain the trading, political, and military alliances that had developed. As the conflict escalated, Native people had no way to avoid the fight. Their land, villages, and homes all became part of the battlefield. During the war, British and American armies targeted Native communities to weaken alliances between the different armies. Consequently, Native villages were destroyed, families were murdered, and crops were burnt.[82]

In 1783, the Revolutionary War ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris. The peace treaty recognized America’s independence and Britain surrendered all claims to land east of the Mississippi River, which doubled the size of the U.S. This region was mostly inhabited by Native people but after the creation of this treaty, American colonists faced few obstacles in their appropriation of the land. Native leaders were entirely excluded from the treaty process, even though their land was a major component of negotiations.[83] Neither the English nor the American rebels made real efforts to protect the Native people who had fought alongside them. Upon returning home after the war, American Indians who had supported American rebels found that their villages had been taken over by white settlers and their land had been sold. Notions of all Indians as enemies of the revolution were used to justify seizure of their land and exclusion from treaties. The American and British war resulted in land loss, hefty war casualties, the spread of disease, and the devastation of Native communities.[84] To survive, many tribes chose to adapt to Euro-American cultural ways. Key pressures of assimilation were land loss, the hardening of racial formation, disease, war, and a lack of self-sufficiency within indigenous populations that had been dispossessed.

The Post Civil War Treaties and Freedmen/Women Exclusion

A second major turning point began with the U.S. Civil War. The Civil War ended in 1865, resulting in thousands of African Americans and Afro-Natives being freed from enslavement in Native societies, particularly those known at the time as the “Five Civilized Tribes” (Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, Seminole). After the war, the Five Tribes signed peace treaties with the U.S. government to restore diplomatic relations. As indicated in the language of these treaties, the U.S. expected these Native nations to grant citizenship to African Americans who were enslaved there as well as to their descendants.[85] Though Cherokee slaveholders freed their slaves in 1863 in accordance with Cherokee Nation Emancipation Acts and the federal Emancipation Proclamation, many freedpeople in the Cherokee Nation were denied access to tribal land, funds, and rights because of technicalities regarding when they returned to the Nation following the war.[86] The Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations resisted the tenets of the 1866 treaties, enacting codes that denied freedpeople rights to citizenship for nearly forty years.[87] From the perspective of freedpeople, these were cruel and intolerable barriers. From the perspective of tribal leaders, Native nations were being pushed into signing treaties that infringed upon their political sovereignty and their control of the tribal land base. The emancipation of thousands of freedpeople in Indian Territory and onset of federal Reconstruction led to increased U.S. government involvement in Indian Territory. In addition, African Americans escaping violence in the white South set their sights on Kansas and then Indian Territory, where they could marry into freedmen and women families, obtain land, and build new and safer lives. The treaties guaranteeing Black inclusion and residency rights contributed to the ever-growing tensions between formerly slaveholding Native Americans and freedpeople as Native nations witnessed their land being encroached upon. Black-Native relations continued to worsen into the 20th century when Oklahoma statehood in 1907 emphasized the notion of Black inferiority through Jim Crow policies. Racial tension did not begin with the 1866 post-Civil War treaties, nor did it end with the formal inclusion of freedpeople into American Indian citizenries (a feat still not fully accomplished for descendants in every former slaveholding Native nation).

Buffalo Soldiers in the West

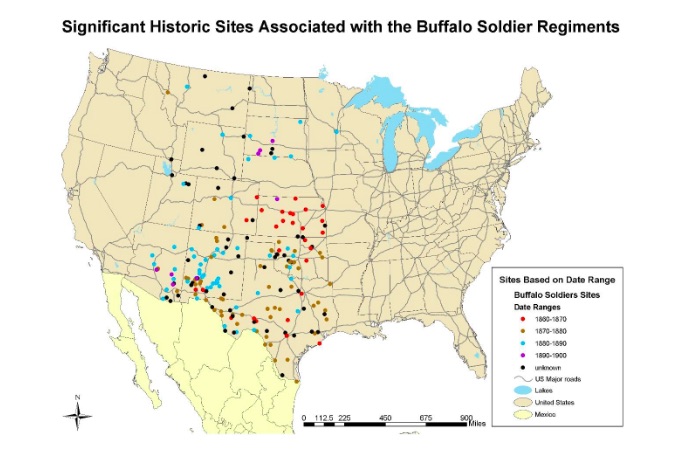

A third critical turning point in Native-Black histories was Buffalo Soldiers’ arrival in the West, which represents the major form of Black involvement in state-sponsored wars and violence against Native people. While Black people had served in the Revolution, the War of 1812, and the Civil War, they had never been recruited by the regular army during peacetime before the late 19th century. Immediately following the Civil War, the army faced expansive responsibilities across most of the continent, including a precarious situation with Mexico and France along the Rio Grande, occupation of the former Confederacy, and the threat of hostility from American Indians across the vast U.S. West. In need of an expanded military, Congress turned to Black regulars as a practical and economic means to preserve their continental empire, particularly in the West where desertion rates among white soldiers were exceptionally high. In July 1866, Congress passed an army reorganization bill that created six all-Black regiments (two cavalry and four infantry), making Black soldiers 10% of the peacetime army. In 1869, after Congress made reductions to the entire army, Black soldiers could enlist in four possible units, the 9th and 10th Cavalry or the 24th and 25th Infantry. In the second half of the 19th century, those units engaged in direct combat with American Indians, restricted the movements of Indians off reservations, sought to keep white intruders off reservations, guarded property during labor strikes, protected railroad surveyors and tracklayers, built roads, strung miles of telegraph and telephone wire, and executed a host of other tasks.[88]

Between 1866 and 1900, there were around 3,000 Black men enlisted in the U.S. army at any one time, amounting to around 14,000 total Black soldiers throughout the period.[89] These “buffalo soldiers” (a term of uncertain origin usually attributed to Plains Indians that encountered Black soldiers on the battlefield) played an instrumental role in securing western North America for the United States and in shaping its character for the foreseeable future. In 2002, a joint venture between Howard University, Haskell Indian Nations University, and the National Park Service identified 250 sites in the twelve states that Buffalo Soldiers played an active role in affairs (see map below). While dispersed across the American West, those soldiers were mainly concentrated in the states of Kansas and Texas, the territories of Oklahoma, Arizona, New Mexico, Nebraska, and the Dakotas, where they executed the decades-long effort to diminish Indian presence and strengthen mostly white settlements. For example, after Chief Victorio, a Warm Springs Apache, refused to resettle his people onto a reservation in Arizona, Black soldiers in the Ninth Cavalry pursued him across the New Mexico Territory for six years. Eventually, after substantial bloodshed, the Ninth Cavalry pushed the surviving Warm Springs Apaches into permanent hiding in northern Mexico in 1881. Nine years later after U.S. troops massacred hundreds of Sioux men, women, and children at Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, the Ninth Cavalry was sent to Nebraska, where they forced over four thousand American Indians onto the Pine Ridge Reservation.[90] These are just two of many examples in which Buffalo Soldiers inflicted violence on Indians, compromised their economic and subsistence strategies, and hastened the despised shift toward reservation life. The Buffalo Soldiers’ activation in the Indian wars is an example of the U.S. government’s strategy of using Blacks to quell Native resistance, which stoked suspicion and conflict between the two groups.

Query 4: Indigenous Land Claims and Settler Communities

Emily Johanson, David Schuberth, Samara Jackson Tobey, and Dylan Nelson

This section of the essay will address three key themes regarding land: the role of settler society in the removal and redistribution of land and power, the role of land as a sacred space and how this intersects with fishing and hunting rights, and the recent fight to maintain land rights on the Northern Plains and along the proposed Dakota Access Pipeline.

The Settler Society

As noted in Query 2, European colonialism was built on and enshrined an ideology of marginalization and destruction. The focal point of that ideology was an understanding of land and the natural world that placed certain beings and ways of life outside of the civilized, human world and therefore outside of moral consideration and political rights. The imported European land philosophy emerged out of the intellectual and philosophical movement known as the Enlightenment, which privileged reason and progress. The ideas of the English philosopher John Locke, particularly his principle of improvement by which private property emerged from European labor that transformed “wilderness” into productive agricultural communities, were instrumental in North America. Throughout the colonial period, Euro-Americans regarded land as an object to conquer and possess that governed access to political, economic, and social power. The dominion over nature that Euro-American colonists imagined prescribed a social hierarchy in which American Indians and Blacks eventually lived at the mercy of military and political apparatuses, which have been described as the settler society, designed for the perpetual expansion of this civilizational model.

In her book, City of Inmates, historian Kelly Lyttle-Hernández demonstrates how this settler society works to justify prejudice, separation, and incarceration. Lyttle Hernández writes that U.S. “[…] cultures and institutions are rooted in a particular form of conquest and colonization called settler-colonialism” that differs from regular colonialism in its focus on land acquisition instead of labor and resource extraction. “On that land,” Lyttle Hernández explains, settler-colonists “envision building a new, permanent, reproductive, and racially exclusive society.”[91] The goal of the settler society is to maintain power and to eliminate outsiders or potential threats. The period of American colonial history saw the attempted elimination of Native peoples and forced labor extraction from Black people via slavery, both key ways to accumulate land and to benefit from land resources in a settler society.

Settlers (usually but not always white) attempted to absorb land to attain power, a trend that tracks through all American history as notions of “manifest destiny” led to further expansion and elimination. The concept of the settler society creates a frame for understanding problems in the ‘now’ and seeing how common ground may be found in defense of land (and people). Framing the history of the United States as a settler society also sheds light on the ways that conflicts have arisen between marginalized groups over land access and rights —including fishing & hunting rights and clashes over environmental protection. The settler society foments friction between indigenous peoples (whose land was taken) and racialized minority groups (who have been separated from their former homelands, sometimes through force, as in the case of African Americans).

The Dawes Act of 1887 (The Indian General Allotment Act)

Named after its author, Senator Henry L. Dawes, The Dawes Act of 1887 (also known as The Indian General Allotment Act and the Dawes Severalty Act) was the most influential piece of legislation regarding Native American land division and reallocation. The Dawes Act was drafted as a means of partitioning allotments of common tribal land to individual Native households. The original draft included guidelines for how much land would be allotted and to whom. 160 acres of land would be given to heads of households, 80 acres would be granted to each unmarried adult, while 40 acres would be assigned to minors. These amounts were to double if the land was only suitable for grazing. The law stipulated that land could only be allotted if the property went on to be used (i.e. cultivated) for twenty-five years and had previously been federally-owned (therefore not subject to taxation). After the twenty-five-year period, the land recipient would become a U.S. citizen and be subject to federal, state, and local laws including taxation. Congress did not pass this act until it was amended to state that “surplus” lands not allotted to Native people would be made available for purchase to settlers. When the act originally passed, married Native women were ineligible to receive land, but this was amended in 1891 to ensure equal treatment of all Native American adults. This amendment to the act also stated that the size of allotments were to be cut in half.

The Dawes Act was among deliberate efforts to “civilize” American Indians. By measuring Indian “progress” according to how thoroughly Indians assimilated into white American culture and lifeways, the civilizing mission sought to eliminate the most potent threats to the settler society’s existence, namely Indian landholding, political organization, and distinct customs and identities. By 1932, the federal government maintained control of nearly half of land formerly held by Indians and the rest was sold off to white settlers.[92] Through the Dawes Act, the United States government effectively gained control over Native lands and laws while expanding its own territory. While all Native Americans, regardless of property ownership, were granted United States citizenship in 1924, the Dawes Act and the previous century of state violence had left Indians with meager access to land and capital and permanently tied them to the political culture of assimilation.