Detroit Study Club

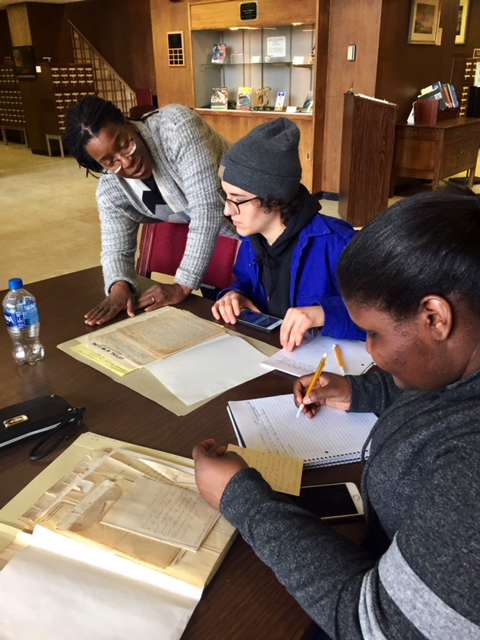

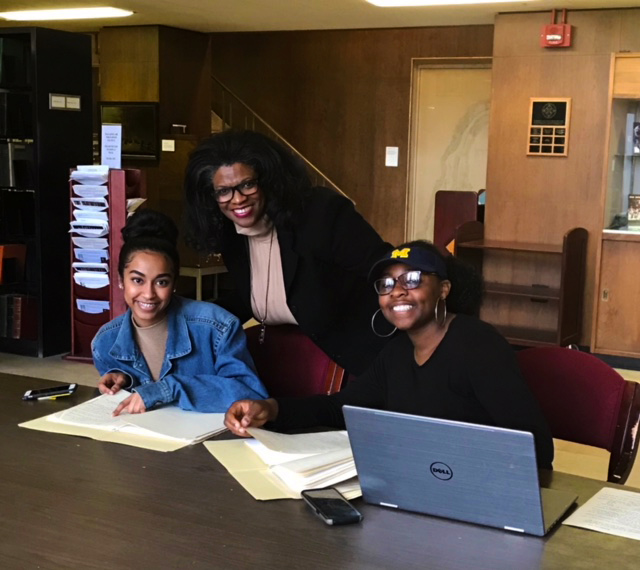

In the winter of 2018, first-year students (pictured above) in the course “Images of African American Women” at the University of Michigan conducted original research to create a Wikipedia entry at the request of an African American women’s community group. That group, the Detroit Study Club, had existed for over a century but was not widely known beyond its local context. The material below represents the students’ compilation of several archival discoveries. The longer essay co-written by the class, which includes greater detail, contextualization and discussion, may soon appear on Wikipedia. In the meantime, read our summary below for more about the Detroit Study Club.

The Detroit Study Club

By Students in the Course “Images of African American Women,” University of Michigan

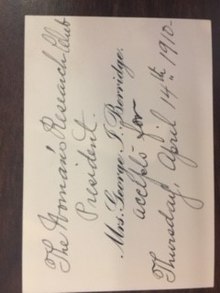

Invitation to DSC founder Gabrielle Pelham to attend a Jewish Woman’s Club meeting. Courtesy of Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

On March 2, 1898, Michigan music educator Gabrielle Pelham invited five friends to her Detroit home for the purpose of study. These friends were Fannie Anderson, Sarah Warsaw, J. Pauline Smith, Mrs. Wil Anderson, and Mrs. Tomlison. Upon their meeting, the new association that would later be called The Detroit Study Club was born. Pelham and her guests gathered regularly to expand their knowledge of cultural and social issues. Pauline Smith, one of the original five guests, served as the club’s first president. They began by immersing themselves in writings of the popular British poet Robert Browning and therefore first called their group The Browning Club. After five years of convening, they broadened their reading list beyond Browning but agreed to set aside one session per year for further consideration of the author’s work. Together, they formed an organization that was distinctive while also being part of the national movement of black women’s clubs.[1]

Today, the Detroit Study Club looks often to its roots. Members still honor early twentieth-century traditions, including the commitment of one meeting annually for discussion of Robert Browning’s writing and the strict use of Parliamentary procedure as detailed by Emma Fox in the 1920s. Club members of the 1890s were well educated and economically privileged women whose families had often been generations removed from slavery. The families of founding members were intimately tied to the black Underground Railroad activist network and the later black professional class of Detroit, both as wives and children of prominent men, and more rarely, as professionals in their own right. Descendants of Asher and Catherine Aray, such as their granddaughter, Mrs. John A. Loomis, and descendants of William Ferguson, continue to serve as officeholders and active members in the Detroit Study Club in the present day.[2]

Mrs. Sammuel H. Russel, 6th President. Courtesy of Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

As Midwest members of a nation-wide black women’s club movement, the Detroit Study Club women had interest not only in matching the cultured refinement of white women in the city, but also in furthering the progress of the black race. They sought to do the latter by hosting influential thinkers and reformers working toward racial uplift. On Thursday, April 14th, 1910, the club hosted a “Celebration of Reciprocity Day” tea in honor of the towering African American educator and orator, Booker T. Washington. Washington was to lecture and then respond to questions, promoting general conversation among attendees. Twenty-seven women’s clubs and organizations in the state were invited to the formal event and twenty-two happily accepted. Washington’s commitment to black education dovetailed with the primary focus of the Detroit Study Club, and their interest in hearing from him reflects a support of his views shared by many black club women around the country. Proceeds from the event went toward the education of underprivileged students to increase their opportunities to attend and succeed in school.[3]

In addition to hosting Booker T. Washington, the Detroit Study Club also engaged in fruitful dialogue with another major figure of the Progressive Era and the black intelligentsia: Professor W.E.B. DuBois.

The Detroit women’s communication with both these black intellectual leaders supports the view of historian Brittney Cooper, who argues that black club women saw spaces of overlap between the ideas of two men who have too often been represented as having diametrically opposed views about strategies for improving black lives. The minutes of the Detroit Study Club record the receipt of a letter from W. E. B. DuBois in 1909. DuBois reached out to club members first in this letter exchange, asking the women for information relating to charities and other institutions maintained by African Americans. The group responded in a return missive, and members extended thanks to an executive board member for her outstanding correspondence with DuBois.[4]

While W.E.B DuBois was recognized as an advocate of the Black women’s clubs, his support may not have been as robust as the women involved in the movement would have hoped. In a brief dispatch published in 1899, DuBois praised the National Association of Colored Women for their physical appearance and feminized southern accents, rather than the intellectual capital they provided to the racial uplift movement. DuBois contrasted the efforts of black women’s clubs with that of the NAACP, which was male-dominated at the time. In his eyes, black women were aesthetically pleasing symbols of the fight while men carried out the masculinized work of putting ideas into action. Even as black women organizers in Detroit and elsewhere ably engaged with men like DuBois, they were acutely aware of gender prejudice among the leading men of their race.[5]

Private invitation to other Detroit women’s clubs to meet members of the Women’s International Press Union, 1900. Courtesy of Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

Their planning of a speech by Washington and written exchange with DuBois show the Detroit Study Club members to be women of letters and ideas, but they also devoted themselves to community outreach and the promotion of the public welfare. One of their greatest ventures in this regard was the creation of the Phillis Wheatley Home for Aged Colored Ladies in Detroit, co-led by Study Club member and teacher Fannie Richards and Ypsilanti resident Mary McCoy (who was married to the inventor Elijah McCoy). Fannie Richards served as the first president of the Wheatley Home.[6] The Phillis Wheatley Home was a special place of service for the Detroit Study Club women, especially during Christmas-time. They used this communal domestic space to express care and generosity for other black women in need. Members of the club were also involved in raising funds to save the Frederick Douglass home in Anacostia, VA, which is currently a National Historic Landmark managed by the National Park Service.[7]

In the twenty-first century, the Detroit Study Club continues its outreach by upholding traditions of educational uplift and community affirmation. The club serves as a reading and current affairs group, as well as a social support network for its members. Study Club women are also a wellspring of inspiration and advancement for the larger community, contributing through their professional endeavors in multiple fields. Current members pride themselves on taking time to continue older traditions that showcase black civility and grace, such as penning congratulatory notes when students stand out for their intellectual accomplishments in the Detroit area. When the University Prep Science and Math youth chess teams of Detroit won national tournaments in 2016, Detroit Study Club members delivered handwritten congratulatory notes and hosted a reception for the champions.[8] Among black women’s clubs, the Detroit Study Club stands out for its longevity. Members have been convening, reading, expanding their minds and contributing to community growth for more than a century. Committed to directing their own intellectual and spiritual development, these women launched an association that began with studies of the literary arts and later extended into community welfare work. In the decades after its founding, the Detroit Study Club was shaped by a fierce passion for elevating the individual life of the mind and bettering the social life of the black family and community.

Mrs. Margaret Ward Thomas, 22nd President (right); Victoria McCall Anderson Davenport, member (left); Miss Edythe Thomas, 40th president (top). Courtesy of the Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

The Detroit Study Club has been recognized nationally and locally. President Bill Clinton commended the club on May 10, 1999 for one hundred years of service, cooperative spirit, and strength of conviction. In April of 2016, the Historical Society of Michigan honored the Detroit Study Club with the Milestone Award. Congratulating the club and its then President Roxane Whitter Thomas on over a century of service to Detroit and the larger Michigan community, the Historical Society plaque lauds the organization’s contribution to state vitality and growth. The Study Club members believe they are the first African American women’s club to have received this recognition. During their centennial anniversary year, then president Dorothy Kispert described the Detroit Study Club as eager to face a new millennium with renewed commitment to carrying forward its longstanding values. Members of the club’s current historical committee, Cynthia Long and Terees Western, join past president Dorothy Kispert, current President Eldora Dodie Stevens and current Vice President Linda Williams Bowie in pledging the Detroit Study Club’s continued devotion to educational enrichment and involvement in the social issues impacting black America and the city of Detroit.[9]

Acknowledgments

Marker for Michigan Centennial Organization issued by the Historical Society of Michigan. Courtesy of Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

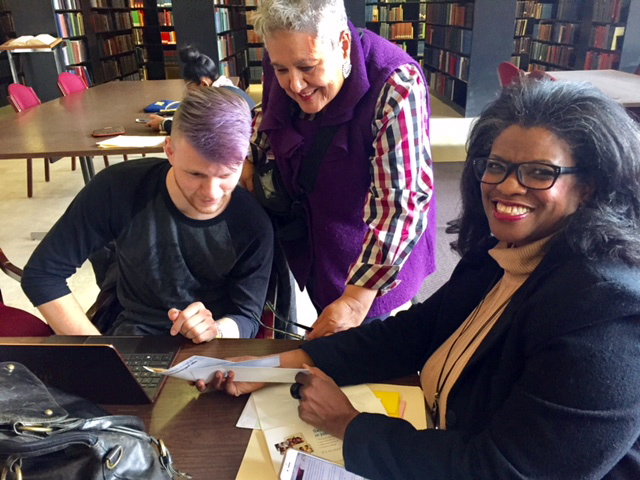

This class project would not have been possible without the will and support of the Detroit Study Club. We depended on the crucial guidance of archivist Dawn Eurich, the assistance of other staff members, and the support of director Mark Bowden at the Burton Historical Collection of the Detroit Public Library. Our research in the BHC was funded by the Department of American Culture at the University of Michigan – Ann Arbor.

The student authors of this essay and the Wikipedia entry on The Detroit Study Club would like to especially thank Cynthia Long and Terees Western, members of the Detroit Study Club historical committee, and Linda Williams Bowie, Detroit Study Club Vice President, who provided inspiration, encouragement, oral histories, and photographs. We are grateful to Professor Tiya Miles, who motivated and guided us, and to Dylan Nelson, who helped organize our archival research efforts, supplemented our class writing on the Arays and the McCoys, and co-edited our essay. Most importantly, our completion of this project could not have been accomplished without the support of every member of our class, American Culture 103, “Images of African American Women”: Ayodele Adelaja, Leila Akan, Alexis Alexander, Mariah Benford, Christian Blakely, Jolyna Chiangong, Nicole Doucet, Elaine Garjo, Franchion Jefferson, Olivia Katamanin, Katherine Kaufman, Katherine Kuhlman, Malikah Pasha, Lauren Payne, Ryan Sowulewski, Chuxin Wu, and Darlena York.

- Tiya Miles and American Culture 103 students, interview with Detroit Study Club History Committee members Cynthia Long and Terees Western, Detroit Public Library, April 6, 2018, Detroit, MI. Jane R. Thomas, “The Detroit Study Club: A History,” The Detroit Study Club 100th Anniversary Celebration [booklet] (Detroit, MI: The Detroit Study Club,1999). “Reminiscences,” (March 2, 1928), History of the Detroit Study Club, and “A History of the Detroit Study Club,” (May 1949), Lillian Bateman Johnson Collection, History of the Detroit, Study Club, MS/Detroit Study Club Papers, box 2, folder 2, Burton Historical Collection (BHC), Detroit Public Library, Detroit, MI. Cynthia Long to Tiya Miles, email exchange on Detroit Study Club first members, April 11, 2018.

- Tiya Miles and American Culture 103 students, interview with Detroit Study Club History Committee members Cynthia Long and Terees Western, Detroit Public Library, April 6, 2018, Detroit, MI.

- Correspondence, MS/Detroit Study Club Papers, 5:4, BHC. Miles and American Culture 103, interview with Long and Western, Detroit Public Library, April 6, 2018, Detroit, MI. Brittney C. Cooper, Beyond Respectability: The Intellectual Thought of Race Women (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2017), 25-26. Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880-1920 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993), 158-159, 213. John B. Reid, “A Career to Build, a People to Serve, a Purpose to Accomplish,” in Darlene Clark Hine ed., We Specialize in the Wholly Impossible: A Reader in Black Women’s History (Brooklyn, NY: Carlson, 1995), 312.

- Cooper, Beyond Respectability, 25-26. Minute Book, 1909-1912, 3:2, MS/ Detroit Study Club Papers, BHC. “History,” Detroit Study Club History, 2:2, MS/ Detroit Study Club Papers, BHC.

- Cooper, Beyond Respectability, 33. Higginbotham, Righteous Discontent, 120-121.

- Thomas, “A History,” Detroit Study Club Anniversary booklet, 18; Boyd, Black Detroit, 54, 84; Reid, “A Career to Build,” 313; Salem, “National Association of Colored Women,” 847. Minute Book, 3:6, MS/Detroit Study Club Papers, BHC.

- Dorothy Salem, “The National Association of Colored Women,” in ed. Darlene Clark Hine, Black Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia (Brooklyn, NY: Carlson Publishing, 1993), 849. Brent Leggs, “Growth of Historic Sites: Teaching Public Historians to Advance Preservation Practices,” The Public Historian 40:3, August 2018 (forthcoming and cited by permission of the author and journal), 1, 22. Thomas, “A History,” Detroit Study Club Anniversary booklet, 18. https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/cultural_diversity/Frederick_Douglass_Historic_Site.html. Accessed April 12, 2018. http://allenbrowne.blogspot.com/2012/09/cedar-hill.html. Accessed April 12, 2018.

- Miles and American Culture 103, interview with Long and Western, Detroit Public Library, April 6, 2018, Detroit, MI. Ann Zaniewski, “Detroit youth chess teams bring home national awards from competition in Nashville,” Detroit Free Press, May 16, 2017.

- President Clinton letter: Detroit Study Club Anniversary booklet, inside front cover. Michigan state honor: Detroit Study Club Anniversary Exhibit, Burton Historical Collection Glass Case, Detroit Public Library. Rebecca Ten Brink, Historical Society of Michigan, conversation with Tiya Miles, May 2, 2018, Ann Arbor, MI, http://hsmichigan.org/programs/milestone-awards/. Carrie Hall, “Detroit Study Club Centennial Award,” photo gallery, Hour Detroit, May 17, 2016. http://www.hourdetroit.com/Hour-Detroit/Party-Pics/Detroit-Study-Club-Centennial-Award/ . Dorothy Kispert, “A Message from the President of the Detroit Study Club,” Detroit Study Club Anniversary booklet, 13. Miles and American Culture 103, interview with Long and Western, Detroit Public Library, April 6, 2018, Detroit, MI.