Reviews of All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, A Black Family Keepsake

Book Review: All That She Carried — the extraordinary history of a mother’s gift

Tiya Miles traces a simple cotton sack across generations of enslaved women to tell a powerful story of love and survival

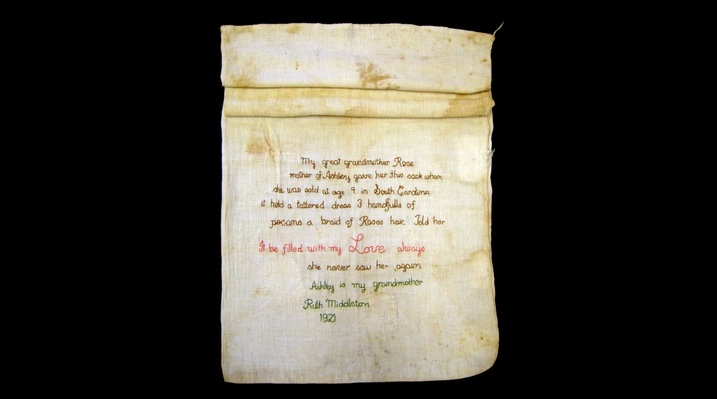

In 2007, at a flea market near Nashville, Tennessee, an extraordinary object was discovered among a bin of old fabrics. It was a cotton sack, dating back to the mid-19th century, rather threadbare and unremarkable bar a moving and intimate hand-stitched inscription documenting a mother’s love:

My great grandmother Rose

mother of Ashley gave her this sack when

she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina

it held a tattered dress 3 handfulls of

pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her

It be filled with my Love always

she never saw her again

Ashley is my grandmother

Ruth Middleton

1921

The historical record is typically written by those with power. In the case of the antebellum South, that generally means white, male slave owners. In its poignancy and detail, Ruth’s account, painstakingly embroidered on to fabric — the line “It be filled with my Love always” emphasised by bright red thread, the “Love” bigger and bolder than all the words surrounding it — is a powerful dissenting narrative, “a baseline rebuttal to the reams of slave-holder documents that categorized people as objects”, as Tiya Miles puts it in her sixth book, All That She Carried, published to great acclaim in the US in 2021.

As this extraordinary study goes on to show, it’s also a means by which to illuminate the experiences of millions of enslaved people whose voices have been silenced.

Traces of Rose and Ashley are all but nonexistent, but Miles doesn’t allow this to discourage her. A Harvard history professor who specialises in recovering the lives of Native Americans, African Americans and women, she is well versed in what she calls the “obfuscations” of the archive. This is not “a traditional history”, she warns her readers in the introduction. “It leans toward evocation rather than argumentation and is rather more meditation than monograph.”

If this might hint at a lack of scholarly rigour, it’s misleading. Not only is the book grounded in extensive and diligent research, but Miles’s argument for turning to a writing practice inspired by the work of the African-American cultural theorist Saidiya Hartman — one that uses imaginative licence in the face of archival gaps — is entirely convincing.

As such, she is unafraid of evocative language. Ashley’s “tattered” dress is, she says, a “fabric scar, a second skin, a shield [ . . . ] a sign of women’s lives frayed by slavery but nevertheless resplendent with beauty”. Neither does she shy away from poetic allusion. She envisions Ruth as a “storyteller” who “imbued a piece of fabric with all the drama and pathos of ancient tapestries depicting the deeds of queens and goddesses”.

Such artistic forays are always tethered to fact, and Miles employs speculation with impressive restraint and precision. Combing the records that do exist, she constructs portraits of Rose and Ashley in the shadows, reflections and elisions of what has been documented; triangulating existing records of the lives of other slaves both male and female (though obviously with an emphasis on the latter) in the years immediately preceding the Civil War, to fill in the blanks.

Most important, though, is the sack itself, an archive all its own — “at once a container, carrier, textile, art piece and record of past events”, which today belongs to the Middleton Place Foundation in Charleston, South Carolina. Miles structures the book around a close reading of it and its contents — long since removed, of course, but the list provides “a nearly unparalleled opportunity for insight into the lives of enslaved women”.

We get a history of the cotton trade; a consideration of the strict categorisation of the kinds of materials enslaved people were permitted to wear; a reflection on the food they ate (or weren’t allowed to eat); and the symbolism of hair, “a medium through which captors and captives fought for corporeal as well as psychological control” — a shorn female slave’s head was a sign of punishment.

Miles also discusses the value of the personal possessions of those who are considered property, and the broader trauma of mothering “under the constant shadow of loss”. When children like Ashley were sold off as chattel, it was part of a mother’s job to arm their child as best they could against this “private apocalypse”. Ruth’s very existence, of course, is proof that Ashley did endure, even though Miles can’t say for sure what happened to her.

Her impressive academic credentials aside, it takes a visionary mind to do what Miles has done in All That She Carried. First and foremost, this book pays homage to the lives of Ashley and Rose. But Miles has also managed to transform “the unspeakability of slavery’s humiliations and corrupted relationships” into a work that stands as a testament to the humanity enslaved people were so brutally denied.

— By Lucy Scholes. Read the review as it appears in the Financial Times.

Book Review: A humble cloth sack tells a story of enslavement and separation

In 2018, the Trump administration instituted a “zero tolerance” immigration policy that separated at least 2,800 children from their parents at the southern border. Many Americans were appalled, perceiving the actions as going against the country’s values. But in fact, ripping families apart is deeply woven into the fabric of American history. Whether because of boarding schools for Native Americans in the 19th and 20th centuries, forced Mexican repatriation during the Great Depression, or the enslavement of Indigenous and African people from the colonial period on, parents and children were routinely separated. For more than 200 years, untold numbers of babies, toddlers and youngsters were torn from their families as enslavers sold them or gifted them to heirs. Others saw their parents put up for sale. How children and adults dealt with the constant threat and reality of forced abandonment and separation is hard to imagine. Tiya Miles, a professor of history at Harvard University and the author of five previous books, comes close. Her lyrical account presents the obscene inhumanity of slavery while celebrating the humanity of its victims.

“All That She Carried” is organized around a rare and haunting object. In 2007, a White woman bought an old cloth sack, once used to hold cotton or animal feed, at a flea market. The words embroidered on the sack made her realize that she had found something special. She sold the bag to Middleton Place plantation outside Charleston, S.C., which eventually loaned it to the National Museum of African American History and Culture in D.C., where it is currently on display.

The sack was embroidered in 1921 by a woman named Ruth Middleton with 10 short lines relaying the history of her female ancestors, including her grandmother Ashley. Nearly 70 years earlier in South Carolina, this Ashley, just 9 years old, was handed the sack by her enslaved mother, Rose, as she was about to be sold away. In the sack, Rose had placed a folded dress, three handfuls of pecans and a braid of her hair, and “told her” — Rose’s words recorded in red stitches on the bag by her descendant — “It be filled with my Love always.” Ashley never saw her mother again.

Miles combed South Carolina plantation records to find information about Rose and Ashley, and she weaves her findings into fascinating and informative stories. Yet in the end, her research, while highly plausible, could not be conclusive. Systemic racism extends to the archives. African Americans are either not present in the documents, or they are rendered through White eyes. To circumvent such “archival diminishment,” Black feminist historians, Miles among them, are developing innovative ways to get at the past experiences of Black women. Miles explains in her introduction that her methods included “stretching historical documents, bending time, and imagining alternative realities into and alongside archival fissures.” In addition, she examined actual items enslaved people made and used, uncovering how these keepsakes expressed their experiences and histories. The result is a deeply layered and insightful book.

Miles places Rose and Ashley’s story in the larger history of Indigenous and African slavery in South Carolina from the 17th century through the Civil War and emancipation. The lives of Rose, Ashley, and Ashley’s daughter Rosa and granddaughter Ruth are traced through Reconstruction, Jim Crow segregation, the Great Migration and post-World War I African American society in Philadelphia, where Ruth moved in her teens. Where historical information is lacking, Miles effectively draws on novels and the published and unpublished memoirs of numerous African American women to imagine what the archives cannot reveal.

Miles explores in depth the meanings of the items Rose placed in Ashley’s sack. A dress, for instance, not merely protected a daughter from the sun or the cold but provided a shield, however flimsy, against the sexual predation and assault African American girls and women routinely faced. Nuts were a “survival food,” packed with calories that might relieve hunger for a spell. Pecans could also be traded as they were still a luxury in the South. Hair held great symbolic meaning in the 19th century, not only for African Americans but for Whites, too. And all three items — clothing, food and hair — figured prominently in the uneven power struggles between enslavers and enslaved.

But the book is more than a compelling primer on African American history or an indictment of America’s moral failures. Throughout, Miles reflects on love. The love of enslaved mothers for their children. The love of the author for her grandmother. The love with which enslaved women’s hands wove fabric, sewed clothing and stitched quilts. These items helped their families to survive but also served as mnemonic devices that combated the erasure of their histories, their existence. In the hands of a gifted historian like Miles, such beloved things form an alternative archive from which to restore Black women’s past emotions and experiences.

Equal measure historical exploration, methodological experimentation and moral exhortation, Miles calls her work a “meditation” rather than a monograph. That seems right, and while it may not be traditional history, it is certainly great history. “All That She Carried” is a broad and bold reflection on American history, African American resilience, and the human capacity for love and perseverance in the face of soul-crushing madness.

It seems that some would want to forbid the teaching of books like this one in our schools and universities. Those trying to distract us with the bugaboo of critical race theory fail to see how much we all need not only a reckoning with slavery and its legacies, but examples of courage and persistence. As Miles reminds us, in the face of the “political and planetary emergency” that confronts us, we all need to pack our sacks and gain the courage to become “love’s practitioners.”

— By Marjoleine Kars. Read the review as it appears in The Washington Post.

Book Review: Mother’s love for enslaved child inspires ‘All That She Carried’

In 2016, the Ossabaw Island Foundation held a coastal nature symposium in Savannah where Tiya Miles and nine other leading historians presented research on the Georgia barrier island’s origins and “how the past has shaped the present and could affect the future.”

Miles, a MacArthur “genius” Fellowship recipient and Harvard University history professor, talked about her research on water’s spiritual and mythological role in the lives of the barrier islands’ enslaved Black people. But a chance meeting at the conference with a Savannah newspaper columnist led Miles on a four-year quest through Charleston, South Carolina, and its surrounding plantations in search of another origin story — that of an antebellum cotton sack embroidered with a tale of pain and love so searing, that to this day the sack seems to carry the weight of spirits and myth.

“All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake,” (Penguin Random House, $28), is Miles’ deeply and lovingly researched account of a cotton sack filled in desperation and despair by an enslaved Black mother named Rose in Charleston. The bag was her parting gift to her 9-year-old daughter, Ashley, as the little girl was about to be sold in the early 1850s to another plantation.

At the time, the sack was unremarkable, a rough, cotton duffle that probably had once held seeds or grain. Next to Ashley, it probably looked about the size of a large pillow case. Inside it, Rose placed three tangible things that might be no less than salvation for a child about to be made, essentially, motherless: a ragged dress, three handfuls of pecans and a braid of Rose’s hair. The bag’s empty space was filled with something only Ashley could see and feel: her mother’s love.

We know this because four generations later, in Philadelphia in 1921, Ashley’s granddaughter Ruth Middleton embroidered these words on the sack, which had been passed down from slavery:

“My great grandmother Rose / mother of Ashley gave her this sack when / she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina / it held a tattered dress 3 handfulls (sic) of / pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her / It be filled with my Love always / She never saw her again / Ashley is my grandmother / Ruth Middleton 1921″

By the time Miles saw an image of the sack online, it was part of the permanent collection of the Middleton Place Plantation, outside Charleston, and was on loan to the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. Seeing the image of the worn, patched sack and how Ruth’s embroidery “entered her family’s humble sack into the written record from which histories of the nation are made,” Miles has sought to make Rose, Ashley and Ruth’s story whole through meticulous research. Or at least as full as plantation ledgers, census records, estate records and newspaper clippings will allow.

As Miles points out, the stories of the enslaved were rarely recorded. Indeed, after years of research and detective work, she could find only a couple mentions of Rose and Ashley in records that listed them as property with an ascribed dollar value. Ashley at 9 years old was valued by her enslaver at $300, not factoring inflation.

But even as a historian’s creed dictates that corroborated facts are the most important ones, Miles honors the women with not only the scant facts she could gather, but also with belief that the story Ruth told was true. To bolster that belief and to fill in the gaps of the record, Miles relies on narratives from the formerly enslaved, primarily those of women, to illustrate what life was like for Black women and girls such as Rose and Ashley. Among them are the narratives of Elizabeth Keckley, seamstress and designer for first lady Mary Todd Lincoln; Harriet Jacobs (”Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl”) and Louisa Picquet, whose hellish life as a “fancy” or sexual slave of three different white men for more than two decades, was told in a book written after she made it to freedom.

For as much as “All That She Carried” is a feminist document of ingenuity, perseverance and abiding care — of not only one mother and daughter but hundreds of thousands of such enslaved women — it is also a lesson on the mechanics of slavery.

Each chapter examines not simply the items in the sack, but the larger story of their role and meaning in the slave trade. We learn that clothing for enslaved people was constructed of the lowest quality, abrasive, dull fabric available and was rarely replaced by enslavers even when they were beyond threadbare.

The pecans were to stave off hunger that was a constant for the enslaved, who rarely were given decent or enough food to sustain them. But it is the discussion of hair, and how it was used by some enslavers as a way to control and degrade the enslaved, that is especially chilling. The episodes bring to mind the contemporary case of a high school wrestling coach having a player’s dreadlocks sheared away before a match because they were deemed unacceptable. In each case, then and now, the degradation was meant to control.

Ashley’s sack was found at a Tennessee flea market about 13 years ago by a shopper who eventually donated it to the Middleton Plantation. While it was on display there, it often elicited tears from visitors, so much so that a curator kept tissues on hand. Miles’ book gets as close as any document can to explaining why the sack remains so powerful. It contains great misery, but it is also a testament to the power of story, witness and unyielding love.

— By Rosalind Bentley. Read the review as it appears in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

The Echoes of Artifacts in “All That She Carried”

Just like Tiya Miles, historian at Harvard University and author of All That She Carried, I grew up in Cincinnati, a city where history, voices and ghosts enter without knocking. For Miles, these echoes are held within her Great Aunt Margaret Stribling’s quilt, for me it is my great grandmother’s silver spoon, and for an enslaved woman named Ashley, it was a cotton sack. These ancestral artifacts, Miles argues, hold not just the power of memory, but act as spiritual and tangible evidence of survival.

All That She Carried centers around one object—Ashley’s Sack; an embroidered cloth sack given from an enslaved mother named Rose to her nine-year old daughter Ashley when she was sold away. The sack contained a dress, a handful of pecans, and a braid of her mother’s hair. The sack was passed all the way down to Ruth Middleton, Rose’s great-granddaughter who in 1921 while living in Philadelphia embroidered the following words:

My great grandmother Rose

mother of Ashley gave her this sack when

she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina

it held a tattered dress 3 handfulls of

pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her

It be filled with my Love always

she never saw her again

Ashley is my grandmother

Ruth Middleton

1921

In the early 2000s the sack was purchased at a flea market for $20 in Nashville. It now sits at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, on loan from the Middleton Place Foundation in Charleston. The sack motivates the book—a lyrical meditation, an excavation of lineages of black women’s thought and practices of survival. Meeting at the nexus of African American Studies, environmental history, and material culture studies, All That She Carried unearths the multiple textures of black women’s experiences, from enslavement to Jim Crow. Light on the jargon and academic opacity, the book reads smoothly, transitioning rhythmically and occasionally poetically from the past to the present.

Miles is additionally the author of a historical fiction book, and her recent research has been invested in an oral history of ghosts. Her use of language often erupts with juicy descriptions and viscerality. Readers will become acquainted with classic slave narratives such as Harriet Jacobs, and other lesser-known figures such as Eliza Potter and Melnea Cass. These sources operate to produce a “chorus of corroboration.” This chorus also includes contemporary black women writers such as Alice Walker, Gayle Jones, Toni Morrison and Octavia Butler. Due to the archival limitations of the sack itself, these other voices operate to bring clarity to the daily lives and experiences of Black women across time and space.

This creative use of sources is greatly influenced by the work of historian Marisa Fuentes, author of Dispossessed Lives, and critical theorist Saidiya Hartman. Fuentes’ method of “reading along the bias grain” and Hartman’s “critical fabulation” play a critical role in the analytic work of All That She Carried. In this methodological shift, Miles follows a turn within the field of Black women’s history which looks to stretch the contours of the archive “to identify the bias grain…the place where the records can be stretched to reveal still more.” Though Miles speculates and creatively uses sources she works with a methodology of care. This care is found in her deliberate and careful attention to detail working to not reproduce any harm to her historical subjects.

All That She Carried locates the spiritual and tangible archive in objects, places, and literature. This is not traditional history; here emotions are held with the same care and consideration as traditional sources. The goal is not simply to uncover the story of Ashley’s sack, but to unpack the meaning of material things in Black women’s lives from enslavement through Jim Crow segregation. How did these material items enable the cultivation of community? Things, objects, and places preserved over time show familial continuity. Miles compels us to consider how objects hold a certain metaphysical space where memories and emotions meet, making them valuable and transformative sites for scholarly focus.

Following the book’s title, the items within the sack, those which were carried, narrate our journey through Black women’s history. This study of material culture illuminates how the dress packed by Rose reflects how enslaved women used everyday objects to resist structures of oppression. The handful of pecans show the importance of the land and specifically Black ecological inheritance. These items also worked to contradict the system of slavery itself by erasing the illusion that enslaved people were themselves property. The terror of familial separation shines through the specific items Rose left for her daughter—some items provided sustenance and protection, while the braid of hair is a tender expression of motherly love and familial ties which slavery attempted to dissolve. For Black families, a group which has historically experienced material precarity, objects hold and symbolize family, survival and strength.

In an attempt to extend the ethical lessons of Ashley’s Sack to our current moment, Miles tends to rely on over-generalizations, stretching the cloth sack across the nation too far beyond its specificity. This decision towards generalization at times erases the specificity of enslaved women’s realities, and the complexity of our past, in favor of a kumbaya-esque “national reckoning” ethos. She cast this historical moment of terror and violence in an instructive manner—arguing that Rose’s story and “Black women of our past can be teachers.” I agree that our ancestors provide tools and strategies to navigate our current reality but caution attempts at removing these lessons from their historically specific context. The beauty in All That She Carried is found in the specificity of Ashley’s Sack and the surrounding narrative which Miles eloquently reconstructs. Black women’s voices, things and lineages deserve space to exist separate from moral imperatives.

Overall, All That She Carried is the epitome of an artifactual Black women’s history, one which begins with a cloth sack but ends with the bodies that held it. The significance of the material object grows from it’s communion with the bodies of Rose, Ashley and Ruth. Their corporal engagement becomes as much of an archive as the cloth sack itself. Miles provides a thoughtful and poignant look into the power of one object in telling the story of a people. Whether a silver spoon, an ancestral quilt, or a cloth sack, these artifacts as archives can change the way history is conceived and shared.

— By Mimi Borders. Read the review as it appears in Chicago Review of Books.

In One Modest Cotton Sack, a Remarkable Story of Slavery, Suffering, Love and Survival

As a historian, Tiya Miles is well aware of the professional obligation to proceed with caution, to keep her own expectations from getting ahead of the material at hand.

But as someone who studies the history of African Americans, Native Americans and women, she has also been forced to confront what she calls “the conundrum of the archives” — the way that written records have favored those who had the means (the training, the status, the money) to document their lives.

Such archives tend to skew toward power, which is to say white and male, making them especially fraught guides to the history of the antebellum South. “It is a madness, if not an irony, that unlocking the history of unfree people depends on the materials of their legal owners,” Miles writes in “All That She Carried,” a new book about women and chattel slavery as framed by a single object: a cotton sack that dates back to the mid-19th century, given by an enslaved woman named Rose to her daughter Ashley.

Decades later, Ashley’s granddaughter Ruth embroidered the sack with an inscription that announces its provenance:

My great grandmother Rose

mother of Ashley gave her this sack when

she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina

it held a tattered dress 3 handfulls of

pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her

It be filled with my Love always

she never saw her again

Ashley is my grandmother

Ruth Middleton

1921The artifact now known as Ashley’s sack is currently on display at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, on loan from Middleton Place in South Carolina, where so many viewers started weeping that the curator handed out tissues beside the display.

Little about the sack is definitively known. It had turned up at a flea market in Nashville in 2007, where a customer found it in a bin amid old fabric scraps. Miles tries to learn and reconstruct what she can, taking care to respect the silences in the historical record while also refusing to abandon Ashley and Rose to “that discursive abyss.”

“All That She Carried” is a remarkable book, striking a delicate balance between two seemingly incommensurate approaches: Miles’s fidelity to her archival material, as she coaxes out facts grounded in the evidence; and her conjectures about this singular object, as she uses what is known about other enslaved women’s lives to suppose what could have been. “This is not a traditional history,” Miles writes in her introduction. “It leans toward evocation rather than argumentation, and is rather more meditation than monograph.”

Still, it contains a good deal of historical sleuthing, as Miles details the search for Rose and Ashley, corroborating pioneering archival work done by the cultural anthropologist Mark Auslander. Rose was an exceedingly common name; Ashley, at least for a girl, was not. A Rose without an Ashley was unlikely to be the Rose that Miles was looking for.

There was one record that turned up both names in an inventory of an estate belonging to Robert Martin of South Carolina shortly after he died in 1852. The death of an enslaver was often a moment of unpredictability and consequent terror for those people he claimed as his property; this was when his estate was most likely to be liquidated or sold off in parts, and children separated from their parents.

Miles, a professor at Harvard and the recipient of a MacArthur fellowship, cross-references her sources, explaining that the odds that we have found the right Rose are “surer but not absolute.” She then looks into the sack itself, using the items that Rose gave to Ashley to unspool several narrative threads. She draws a connection from the sack to the expanding cotton trade; the lucrative mass crop, Miles says, made for an even more brutal and squalid kind of slavery than the established system of rice cultivation on South Carolina’s marshy coast. The “tattered dress” allows her to dilate on how the slave system’s reach extended to state laws codifying the kinds of material that enslaved people were permitted to wear.

Considering the “3 handfulls of pecans,” Miles writes about food and nutrition; pecans would have been a delicacy in Charleston at the time, prompting her to wonder whether Rose may have been a cook. And the braid provides Miles with a chance to write about hair and what it meant — shorn to punish enslaved women, it was also laden with symbolism, a tie between loved ones separated by distance or death.

The trauma of separation — of Ashley from Rose, of daughters from their mothers, of children from their parents — emerges as a central theme of the book, as Miles tries to imagine herself into the lives of the women she writes about. “We must presume that Rose always knew that she would birth a motherless child,” Miles writes. Much sentimentalism has attached itself to Ashley’s sack and the poetry of Ruth’s embroidered inscription, but the sack was originally an emergency kit, born out of despairing necessity. In slavery, Miles writes, mother love would get entangled in matters of survival, and violent discipline was sometimes seen as a form of rescue: “One formerly enslaved woman painfully recalled how her mother beat her in the same sadistic way that her mother had been abused by whites. ‘She would make me thank her for whipping me.’”

Miles traces the lineage as far as she can, up through Ruth Middleton and her daughter, Dorothy, who died in 1988, leaving no heirs. What’s exceptional about Ashley’s sack is that something so intimate was preserved in this way — pressed by a mother into her child’s hands and passed on, so that a descendant who had heard the oral history firsthand could one day decide to inscribe it onto the object itself. The result, as Miles shows, is a fragile object that contains so much, marking “a spot in our national story where great wrongs were committed, deep sufferings were felt, love was sustained against all odds and a vision of survival for future generations persisted.”

— Jennifer Szalai. Read the review as it appears in The New York Times.

Shelf Awareness Review of All That She Carried

Tiya Miles (The Dawn of Detroit; Ties that Bind), a professor of history at Harvard University, does a difficult task incomparably well in All that She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake. With gentleness and historical acumen, Miles explores the history of this sack, and why it is important in larger terms as part of African American history.

In 1921, Ruth Middleton embroidered a sack that had belonged to her grandmother Ashley, listing what the sack originally contained. Her great-grandmother Rose, an enslaved woman, gave the sack to her daughter Ashley when the nine-year-old girl was sold away from her in 1850s South Carolina. Miles carefully researches the items mentioned in the embroidery: a dress, a handful of pecans, a lock of Rose’s hair, “my Love always.” Miles explores what these would have meant to both Ashley and Rose, and how Rose was doing her best to care for her daughter, even when the terrible system of chattel slavery attempted to thwart Rose’s basic humanity.

Little is known about Rose or Ashley’s early lives, but Miles has found many contemporary accounts to enlighten readers as to what may have gone on in the lives of enslaved women of that era. And she elucidates how a sack was specifically important. As Miles says, “African American things had little chance to last…. How could people who were property acquire and pass down property?” All that She Carried will transport readers to difficult times in American history, and make them think more carefully about all the physical goods they take for granted in their day-to-day lives.

— Jessica Howard, bookseller at Bookmans, Tucson, Ariz. Read the review as it appears on Shelf Awareness.

Publishers Weekly Review of All That She Carried

MacArthur fellow Miles (The Dawn of Detroit) paints an evocative portrait of slavery and Black family life in this exquisitely crafted history. She frames her account around a cloth sack packed in 1852 by an enslaved woman named Rose for her nine-year-old daughter, Ashley, when the girl was sold to a new master in South Carolina. In 1921, Ashley’s granddaughter, Ruth Middleton, embroidered the sack with Rose and Ashley’s story, but it fell out of the family’s possession and wasn’t rediscovered until 2007. Miles pours through South Carolina plantation records to identify Rose and Ashley, and explores the physical and psychological lives of Black women via the original contents of the sack: a tattered dress, three handfuls of pecans, and a braid of Rose’s hair. For example, Rose’s hair sparks a discussion of how enslaved women with lighter skin tones and longer, smoother locks were targeted for sexual assault by white men and violently punished by white women. Filling gaps in the historical record with the documented experiences of Harriet Jacobs, Elizabeth Keckley, and other enslaved women, Miles brilliantly shows how material items possessed the “ability to house and communicate… emotions like love, values like family, states of being like freedom.” This elegant narrative is a treasure trove of insight and emotion. (June)

Kirkus Review of All That She Carried

A professor of history at Harvard chronicles the historical journey of an embroidered cotton sack, beginning with the enslaved woman who gave it to her 9-year-old daughter in the 1850s.

In this brilliant and compassionate account, Miles uses “an artifact with a cat’s nine lives” to tell “a quiet story of transformative love lived and told by ordinary African American women—Rose, Ashley, and Ruth—whose lives spanned the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, slavery and freedom, the South and the North.” The sack, originally used for grain or seeds, was passed from Rose to her daughter Ashley in 1852, when Ashley was put on the auction block, and passed by Ashley to her granddaughter, Ruth Middleton. In the early 1920s, Ruth embroidered its history on it, including its contents: “a tattered dress 3 handfulls of pecans a braid of Roses hair,” also “filled my Love always.” The sack is now on display at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. Like those of most enslaved people, the stories of Rose and Ashley are largely lost to history, but Miles carefully unravels the records and makes a credible case that they may have been the property of Robert Martin in coastal South Carolina. From there, the author moves outward to sensitively establish the context in which the two managed to survive, describing how South Carolina became “a place where the sale of a colored child was not only possible but probable.” By the time Miles gets to Ruth, the historical record is more substantial. Married and pregnant at 16, Ruth moved from the South to Philadelphia around 1920 and eventually became “a regular figure in the Black society pages.” With careful historical examination as well as empathetic imagination, Miles effectively demonstrates the dignity and mystery of lives that history often neglects and opens the door to the examination of many untold stories.

A strikingly vivid account of the impact of connection on this family and others.

Library Journal Review of All That She Carried

Miles (history, Harvard Univ.; The Dawn of Detroit) illuminates the lives of three generations of Black American women via a patched and embroidered cotton sack now displayed in the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Rose, an enslaved woman in South Carolina, filled the sack with what provisions and keepsakes she could for her 9-year-old daughter Ashley, who was sold away from her in the 1850s. Years later, Ashley’s granddaughter Ruth embroidered a narrative of the family history on the sack. From these small clues, Miles delves into Black Americans’ experience of slavery, Reconstruction, Jim Crow segregation, and the Great Migration. With skillful writing, the author carefully explores South Carolina’s history of economic dependence on slavery, and discusses the efforts of enslaved people to obtain sustenance and clothing and maintain family connections. Drawing on scant genealogical records and letters from people who were formerly enslaved, as well as research on ornamentation, Miles creates a moving account of three women whose stories might have otherwise been lost to history.

VERDICT: Readers interested in often-overlooked lives and experiences, and anyone who cherishes a handcrafted heirloom, will enjoy this fascinating book. With YA crossover appeal, the accessible, personal writing sets this book apart.

—Reviewed by Laurie Unger Skinner, Highland Park P.L., IL , Jun 01, 2021. Read the review as it appears on Library Journal Review.